My First Translation Experiences

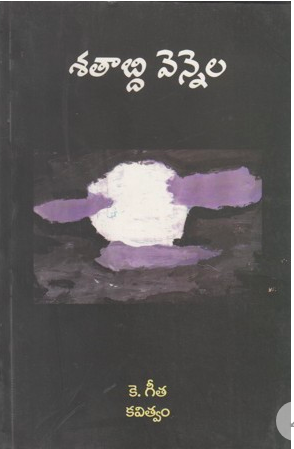

“SATABDI VENNELA” by Dr K. Geeta

-Vidya Palepu

My mother tongue, Telugu, is one of the many Sanskrit child-languages of India, with a literary tradition that dates back to ancient times. As the American-born daughter of two Telugu-speaking immigrants, I am fluent enough to hold a simple conversation, but unable to read or write the script. This article was my effort to engage with written Telugu for the first time in my life.

Unfortunately, an ugly combination of colonization, globalization, the omnipresence of visual media overwritten media, and cultural neglect of the arts have diminished the Telugu-language literary scene to a significant degree. My relatives in India, all fluent readers, and writers of the language, rarely enjoy contemporary Telugu-language novels for pleasure, let alone books of poetry. Luckily, the Telugu community in California where I grew up is large enough that my own mother happened to be friends with a seasoned poet. This was how I got in touch with Dr. K. Geeta

Dr. K. Geeta is an eminent poet and author and the daughter an eminent writer, K. Varalakshmi, a short-story writer whose works address the lives of women in rural areas. Born into a literary family, Geeta began reading poetry from a very young age and eventually went on to earn a Ph.D. in Telugu linguistics at Andhra University. For ten years afterward, she taught Telugu as a full-time lecturer to the eleventh and twelfth grades while publishing a steady body of work throughout. Her inspirations for her poetry are Tilak, Sri Sri and Devulapalli Krishna Sastry.

This collection, titled “Satabdi Vennela” (“Hundred Years of Moonlight”) contains poems that are written entirely in free verse, with a focus on high-register diction over rhyme or meter. In each poem, the narrator uses observations of the natural world as a means to describe their inner life. The poems are filled with descriptive observations, thoughts, or images rather than fully-formed sentences: you see lines such as “the karma of a thousand ages” (poem 4), and “muddy ground that drowns an elephant’s feet,” but neither the karma nor the ground ends up being the subject of a larger statement or thought. In Telugu, these fragmented yet descriptive observations are tied together by a certain melody and rhyme, which, again, is somewhat difficult to maintain in English. Therefore, I tampered with the original line breaks to give the English versions a smoother, more melodic structure.

Poetic Telugu also makes large use of portmanteaus. Because most Telugu words end in a vowel sound, it’s easy to combine two or more words to create a new one that is still grammatically correct. For example, inline 7 of the second poem, we see the word “gaddimokkalannee.” This word combines the words “gaddi,” “mokkalu,” and “annee,” which mean “grass,” “plants,” and “all.” I translated this to “every blade of grass,” which then became “every nameless blade of grass,” when placed in context. Unfortunately, translations of these portmanteaus tend to lose their liquidity. I also chose to use medium-register English words because the high-register Telugu is characterized mainly by its lyrical sound, which could not be maintained in English regardless.

*****

(Poems will continue in the following months-)

My name is Vidya Palepu and I’m a senior at Carnegie Mellon University studying creative writing and technical writing, and I’m passionate about writing and translating literature.