Telugu Women writers-1

1950-1975, Andhra Pradesh, India

(An Analytical Study of Historical, Familial and Social Conditions that contributed to women writers’ phenomenal success immediately after declaration of Independence.)

-Nidadvolu Malathi

FOREWORD BY AUTHOR

In the history of Telugu fiction, one quarter of a century following the achievement of our independence in 1947, from 1950 to 1975, stands out as unique for women’s fiction writing. Contrary to the popular belief that, women’s writing suffered for want of “a room of her own” and/or lack of economic resources, Telugu women writers wrote and published their fiction and gained extraordinary success. Sitting quietly in their kitchens or on the back porch, they wrote and rose to a level where they could dictate the terms to magazine editors and publishers, demand contracts without submitting complete manuscripts, and were paid higher than their male counterparts. Using female pseudonyms by male writers became common during this period. To the best of my knowledge, this is unique and happened only in Andhra Pradesh.

In the past several centuries, women writers were quiet and anchored in religion. Present day writers are highly vocal, and are anchored in ideologies. Historically positioned between these two groups, approximately, one hundred women had created distinctive fiction for a period of two and a half decades. This book is an attempt, however small, to examine their contributions contextually, and demonstrate that they, quiescent on the surface, raised potent questions and expressed unconventional views powerfully in their fiction. I started out with a couple of premises: First, in our culture, which evolved over a period of several centuries, the demographics have played a vital role in formulating the familial and societal values; secondly, women in the past had created their own world imbued with rituals, stories and songs, anchored in religion. Their literature was conformational. Present day writers, beginning in the eighties, called themselves feminists, created a world of their own, with separate magazines, organizations, literature and web sites, anchored in their ideologies. Their fiction and poetry were confrontational.

Positioned between these two groups, the women writers of the fifties and sixties created fiction, taking a significant part of the past tradition in expressing their views yet deviated from the beaten path by laying ground for future writers. It was a period of silent revolution. By that, I mean, they had departed from the traditional past in their choice of themes and language, while continued to cherish the traditional values in real life. Owing to the democratic principles put in place in 1947, the female writers were able to set a new trend and evolve a new culture, and enlist the support of men in the process.

This book addresses one more need. During the nineties, two major works, Women Writing in India (1993) and Knit India Through Literature by Sivasankari (1998), have been published on women’s writing in India. Both the volumes set Telugu women’s writing in the larger context of Indian literatures. This book, on the other hand, offers exclusively an in-depth analysis of Telugu women’s writings, specifically, the phenomenal success of women writers during the period, 1950-1975. This is a product of my personal knowledge and experience, and my standing as a writer during the period under discussion.

Some of my friends in the United States asked me why I had chosen this particular period for my study. The one simple answer is, as a writer, I belonged to that generation, and therefore, am interested in examining how they/we had fared in the history of Telugu fiction. However, more importantly, lack of an all-encompassing critical work on this segment of Telugu literature, namely, the fiction by women writers during the period, 1950-1975, and, thirdly, the fear that it might disappear completely in course of time if somebody had not brought it to the fore. Yet another reason is, while the academic studies are focused on the literature of the past, current literature is featured in magazines and the media extensively, a well-balanced critical analysis of the fiction by women writers of the immediate past is sadly missing.

I must admit that this book raises more questions than provide answers. Due to severe constraints of resources, financial, personal as well as academic, this book is nowhere near being complete. Nevertheless, it provides valuable information and lays the ground for further research. I have put forth a few of my arguments and raised a few questions, with the pious hope that our Telugu scholars will continue to explore and examine this area of study further.

I attempted to trace the historical, social, familial, and economic conditions that contributed to the success of women writers during this period; also, various stages in the development of women’s fiction—from encouragement and praise at home and in the society to reward, and later to ridicule and even to damaging criticism in the final stage.

This is also a personal journey for me. For that reason, I chose the style of narrative nonfiction in this book. The intended audience for this book is non-native speakers and non-Telugu a readers. In that, I may have given more details than necessary in explaining the cultural nuance at times.

Organization: I started out with a brief history of women’s writing identifying the areas their values came from, and discussed their familial and social conditions. In chapter 3, I gave the synopses for a few short stories and novels in order to familiarize the readers with our fiction, assuming that readers are not knowledgeable in Telugu language, and thus not in a position to read the original texts. The synopses are intended to facilitate further discussion in the next chapter. In chapter 5, a brief note on culture and humor was given. in chapter 6, a brief note on the use of language in these stories, and conclusion in chapter 7.

Originally, I planned to include a few stories in translation, in support of my views on the fiction under discussion in this book. However, while finalizing this manuscript for self-publishing, I realized that it would serve my purpose better if I made the stories in translation available separately on my website, www.thulika.net. Links are provided in this book.

Data gathering: I embarked on this journey nearly twenty-five years ago. In addition to reading the books I had access to, I wrote to writers, invited readers to write their opinions on the women writers of the period under discussion, and also traveled to India to interview writers, magazine editors, and publishers. Although I had started in the early eighties, I had to put away for several years in between for personal reasons. Again, in the summer of 2000, I had the opportunity to revive the project. Thus, part of the data may be dated. However, I revised this version, based on the discussions I had with several writers, male and female, in the past six years.

I gave Telugu and Sanskrit words in this book per pronunciation, following our practice in Andhra Pradesh. Being unfamiliar with the use of diacritical marks, and uncomfortable with the transliteration used by some writers, I decided to avoid both the practices.

One more note regarding the form of address. In referring to authors, I used the first names, as is common in our country. For us, the established practice is to address a person by his or her first name, with the suffix garu at the end in the case of adults or strangers.

It is my sincere hope that my venture of recording a piece of history that might otherwise be lost for future generations will encourage scholars to undertake further research.

Kalpana Rentala, a prominent feminist writer from current generation, has taken the time to write the foreword to my book, as soon as I asked. I am grateful to Kalpana Rentala for the informative foreword.

My daughter Sarayu Rao is a big part of my life and activities. She has watched me through my triumphs and travails of this undertaking. Therefore, I asked her what she thought of it. Her observations in her own words are fascinating. Thanks, Sarayu! I wish you all the best in your acting career.

Malathi Nidadavolu

Madison, Wisconsin

July 2008.

***

REVISED, 5 April 2021

After nearly a decade and a half, I got the opportunity to look back and check if there is a need to revise this book. I also found some information that was not available at that time. I am grateful to Telugu Wikipedia for some new information such as dates of births and deaths.

Last week Dr.K.Geeta approached me and sought permission to publish this book as a series of articles on her Magazine, NECCHELI. Additionally, she mentioned that she wanted to preserve it for future researchers. That captured my attention. I was thrilled. Thus I’ve come to decide to go over the text and make changes, edit, fine-tune, and correct as needed.

I am grateful to Dr.K.Geeta for nudging me into reworking this book and bringing an improved version to you.

You may post their comments either here on www.neccheli.com or on, www.thulika.net.

Malathi Nidadavolu.

5, April 2021

HER OWN WORDS, BY SARAYU RAO

(Author’s daughter)

Growing up, my mother always told stories. She and my father kept the oral tradition of storytelling a strong part of our home life. I would come home from school, silent and pouting, because of some petty teenage problem and my mother would see my sullen face and immediately know what was wrong. She was almost clairvoyant, picking up on everything, with or without words. She would look at me and ask what was wrong, hoping I would let her in. I’d respond with a shrug and the word, “nothing” as I sulked into my room and slammed the door. Somehow, despite my hardened efforts to keep her out of my life, she, with her innate subtlety, found a way to make me feel better without me even knowing it. She always had a story. “Do you know the story of how Lord Ganesha came to existence?” She would say. I would shake my head no, and the storytelling would begin. No matter how angry I was, how large the world seemed, or how small I felt, by the end of the story, I was completely drawn in, as the rest of the world melted away. Not only was my mother one of the best storytellers in our household, she was a published short story writer in India as well.

To this day, my mother has proven to be one of the strongest women I know. She is also the most stubborn and headstrong, and she has done a brilliant job of raising a daughter with similar qualities. I remember when I was nine and she and I were walking through a mall in Madison, Wisconsin. We saw the people from a karate school putting on a demonstration. She took the information and immediately signed me up. She knew if I was going to survive in this world, as a woman, I’d better know how to defend myself. She was right. Knowing Tae Kwon Do instilled a confidence in me that has been absolutely irreplaceable.

My Mother is my idol. I will consider myself lucky if I handle my life with the grace, dignity, and pride with which my mother has shown during her years. She has an unbelievable stamina, and never stops trying something new. She is truly a fighter. I’ve yet to see a person approach the tests of the universe with such fervor and determination as she does, never once stopping to become the victim in the story. Her brilliance and sparkle move everyone who knows her to get closer to her. Still she maintains humility, responsibility for herself, and for her actions. She believes in the human voice and the power it has to change the world, she believes in helping each other, she believes in fighting for what is right. If I am making her sound like a superhero, it is because in my eyes she is. And trust me, if you knew her, you’d feel the same.

When my mother told me she began this work, I was thrilled. She has always instilled in me that as a woman in this world it was important for me to recognize my power. She has a sincere belief that women have an inherent strength that we must be willing to possess and share. She taught me to have respect for others’ opinions and voices, but never to lose value in my own.

This book is a beautifully written record of how so many Telugu women in India shared their voices. It helps us to understand the variety of approaches these women used to write the stories we needed to hear. It shows how the world surrounding them affected what they chose to write about, and how they did so. These women were pioneers in their own right, as is my mother. It does not surprise me that she would choose to write about these passionate, bright women who found such intelligent, innovative ways to share their voices, during a time when support for them was beneath surface level. Her fire, her love of writing, and her drive for supporting women, are unending and contagious, as I am sure you will see as you dive into these chapters.

Sarayu Rao Blue

October 2004

*****

1. WOMEN WRITERS

From the Eleventh to Nineteenth Centuries.

This chapter examines the elements of tradition that seeped into women’s writings in the nineteen fifties and sixties with an overspill into mid-seventies. The female writers, encouraged by male social reformers and in an amicable familial environment, created a trend hitherto unheard of in the history of Telugu literature, possibly, in any other Indian literature. A record number of female writers took to writing and produced voluminous amount of fiction. The publishers and magazine editors scrambled for their short stories and novels; and a few male writers took female pseudonyms to get their stories published. To my knowledge, this phenomenon has been peculiar to Andhra Pradesh.

Let me set out with a couple of premises. First, the centuries-old social norms contributed in their own way to set off the women’s fiction in the early nineteen fifties. In our culture, the demographics play a vital role. The greatest resource for us is humans. A family unit consists of two to three generations of people, and personal relationships are developed accordingly in our society. The interaction between family members–caring, sharing, interfering, teasing, and arguing— are all part of everyday life; everybody’s life is everybody else’s business. Our family values and personal relationships, peculiar to our culture, are developed based on our demographics.

Secondly, women have been creating songs and stories in oral tradition in order to express their personal issues and their perceptions of the world around them for centuries. The female writers of the fifties and sixties continued in that tradition; took that part of social norms, which worked for them, and worked them into their stories. However, unlike in oral tradition, they did not limit their fiction to themselves. They wrote about a part of the society that had not been present in the extant fiction, and they wrote from their own perspective.

First, I will briefly trace the relevant elements in the women’s works between the eleventh and nineteenth centuries.

In cultures such as Indian, where oral tradition is predominantly a mode of tutelage and dissemination of knowledge, the short story continues to be one more important medium. Colossal works like Katha Saritsagaram (Ocean of Stories) and Panchatantram (The Five Strategies of Polity) are a series of never-ending stories with several layers of embedded stories and themes. In these works, the narrator starts a story, digresses into another story within the story, and returns to the first story to sum up at the end. In oral tradition, the narration continues for several nights and the listeners will have time to ruminate on the story and make mental notes. Poranki Dakshinamurti, a prominent fiction writer and critic, stated that, “not only Indians but foreigners also agreed that India is the first to explore short fiction. … Our Vedic literature contains stories in their rudimentary form.”

The story of Dudala Salamma of Quila Shapur as narrated in Women Writing in India is a present day example of a story narrated in oral tradition. The narrative highlights a few important features of the oral tradition: [1] Salamma, a woman with no formal education narrated the story. For centuries, formal education for women has been substandard yet their lore, cognition and aptitude to tell a story remained indisputable. [2] Her narrative reflects her courage and strength of character; and shows for who she was-–an active participant in a people’s movement; and, [3] humility, but not self- promotion, has been one of telling virtues of Hindu philosophy for centuries, and by extension, of Indian women. Possibly, for the same reason, we have no biographical details of the narrator Salamma even in this twentieth century account. Telugu women had no problem telling a story. The question of recognition and reward was a moot point even in the sixties.

I intend to address three issues in this book: Telugu women’s education and scholarship (acquisition of knowledge), their status at home and in society, and their talent as writers during the period, 1950-1975. In order to analyze the success of women writers in the fifties and sixties, we need to examine some of the stories surrounding women writers of the past. Those stories tell us how women conducted themselves at home and in society, and despite the odds, continued to write in the beginning and later to publish as well.

Over the centuries, our women acquired knowledge at home through reading books either on their own or with the help of family members. There was evidence of scholarship among upper classes women-–Brahmin [scholars] and Kshatriya [royalty] castes; and later, extended to other economically advantaged classes such as Vaisya [business community] and Naidu [landowner] castes.

Utukuri Lakshmikantamma (1917-1997), a female scholar of high esteem, well-versed in Sanskrit and Telugu literatures, and a noted literary historian of our times, listed more than two hundred women poets extending over ten centuries in her monumental work, Andhra Kavayitrulu [Female poets of Andhra Pradesh], published in 1953. Some of the acclaimed female authors listed in the book were Leelavati (11th century), Tallapaka Timmakka (12th century), Gangadevi (13th century), Atukuri Molla, (14th century or 16th?), Mohanangi (15th century), and Muddupalani (18th century), to name but few. Despite their scholarship, they rarely appeared in public.

They all wrote in Bhakti tradition. Bhakti calls for self-effacement. Whether it is daiva bhakti (devotion to god), pati bhakti (devotion to husband), matru bhakti (devotion to mother) pitru bhakti (devotion to father), raja bhakti [loyalty to the king] or desa bhakti [loyalty to the country, patriotism] the one underlying philosophy in all these is putting the other person’s needs or interests ahead of one’s own.

Humility or self-denigration has been a cultural value for us. For the same reason, I would not read too much into Molla’s comment, “I am no scholar”, “as some critics would have us believe. Male writers also attributed their talent to the divine voice. For instance, Bammera Potana, a male poet (1450-1510), stated at the beginning of his epic, Bhagavatam (The Story of Krishna), that,

palikedidi bhaagavatamata

palikincheduvaadu raamabhadrudata

[It is called Bhagavatham, Lord Rama instructed me to sing].

Even in the modern period, I have come across established writers from the fifties and sixties who would say, “I don’t consider myself a writer.”

Women in the upper classes received support and encouragement from male family members in acquiring knowledge as well as pursuing their literary skills.

*****

(Contd..)

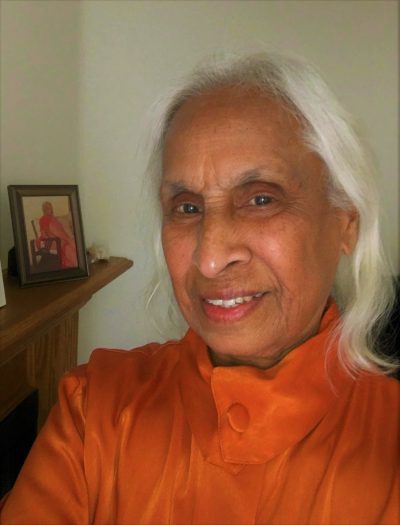

Nidadavolu Malathi born in 1937 to progressive parents, Nidadavolu Jagannatha Rao garu and Seshamma garu. She has Masters’ degrees in English Language and Literature, and in Library and Information Sciences. She has been writing fiction in Telugu since early 1950’s.

She moved to America in 1973. In 2001, she created a website, www.thulika.net, with a goal to introduce Telugu culture and customs through translations of stories and original essays on various topics. She has translated over 100 stories and wrote several critical essays. The website has been a good source for researchers in several universities abroad. In 2009, she started her blog, Telugu Thulika (www.tethulika.wordpress.com) where she has been publishing her Telugu stories, essays and poetry.

Her translations have been published in 2 anthogies, From my Front Porch (Sahitya Academy), and Penscape (Lekhini, Hyderabad). Her short stories in Telugu are published in 2 anthologies, Nijaanikee Feminijaanikee Madhya (BSR Publications) and Kathala Attayya garu (Visalandhra). She also has published eBooks: Eminent Telugu Scholars and other Essays (Non-fiction), All I Want Was to Read, My Litttle Friend (Short Stories.)