Telugu Women writers-3

-Nidadvolu Malathi

Kanuparti Varalakshmamma (1896-1978), erudite writer, gave a compelling account of the social conditions during this period in her article entitled, “Dharmapatni Rajyalakshmamma”:

“After her husband [Veeresalingam] started the widow remarriage movement, it became a fierce struggle for her to maintain her relationship with her natal home. It became impossible to keep her association with both the families—-her parents and the in-laws. If she wanted to stay in touch with her mother’s family, she would have to leave her husband. If she had stayed with her husband, she would have to severe her ties with her parents. After considerable deliberation, she decided to stay with her husband, as was appropriate for a Hindu woman.

“They were ostracized and she had to suffer several hardships as a result. Household help was not available anymore. She had to cook, clean, and fetch water from the river Godavari … the list was endless.

For the same reason, she was not invited to festivities at her natal home or her neighbors … She had to put up with ridicule from the women in her neighborhood silently and with tears welling up in her eyes… In addition, her husband was terribly short-tempered. He would not give her the time of day. If she tried to talk to him, he would say, ‘If you can’t take it, just go back to your mother. Therefore, she had no choice but keep quiet. God only knows how she had endured such hardships.

- R. Narla also expressed similar view on the conditions at the home of Rajyalakshmamma and Veeresalingam. [The original in English].

In a way, she bore greater burden than he had. It was easy for him to offer protection to every child widow that had come to him, seeking help. But it was Rajyalakshmamma who had to feed them, clothe them, and take care of them like a mother. That was not something any ordinary woman could handle … More and more women were coming to them each day. She had to take care of the women from several areas, with different backgrounds and personalities. Normally, it is hard to comfort even one child widow. And, she had to deal with several child widows, with several agonizing stories.

For centuries, Hindu philosophy has been preaching self-effacement through performing one’s duty to family and society. In a familial context, compromise is a cultural value. The term dharmapatni in the title reinforces the same conviction. Literally, the term dharmapatni stands for a woman who carries out her duties in accordance with her husband’s role in society. Rajyalakshmamma lived up to those principles. Harsh as it may sound, the truth is, Veeresalingam honestly believed in what he had been teaching and he made no secret of it. His wife was a living example of what he had expected of a woman.

Not all women followed Veeresalingam’s precepts to the letter. While a few women walked in his footsteps, others demonstrated signs of independent thinking. They managed to process the information in their own way and followed their own hearts, which was in contradiction of Veeresalingam’s precepts.

The story of Battula Kamakshamma (1886-1969), a child widow from a scholarly family, illustrates how women respected Veeresalingam for his wisdom, yet followed their own conscience in practice. She chose not to remarry but helped other young child widows to remarry nevertheless. She dedicated her life to women’s cause.

Kamakshamma’s autobiographical essay, a succinct four-page article, “Smruthulu, Anubhavamulu” [Memories, Experiences] explains how women lived with grace under trying social conditions. I was moved as much by her candid portrayal of herself and the social conditions of her time as her fortitude, determination, and the courage to bring about a change in the lives of other women.

The following two brief passages highlight her perspective.

I was a child widow, about fifteen-years old in 1901-1902. I was living in my uncle’s [father’s brother] home. During those days, wealthy families such as ours were strict followers of tradition. Women could not show their faces in public.

I do not know how it started but the spirit of service was deeply rooted in me. I would never waste a minute of my time. I was always either reading books or helping others. Although my uncle was very kind to me, I could not speak with him about my craving for books.

Some of the members on the library committee noticed that I was reading Veeresalingam’s books and began sending the books on widow remarriage to me, in an attempt to influence my opinion on the subject. I was scared that it could cause problems for me, if my family had come to know about them. Therefore, I gave strict instructions to the peon that he should bring only the titles I had asked for. That was the way it was in those days.

Kamakshamma’s aunt and noted writer, Nalam Suseelamma, also expressed similar sentiment:

In the early days, I was not interested in his [Veeresalingam’s] reform activities. I saw Pantulu garu three or four times but never spoke with him face to face. I could not talk even with his wife, Rajyalakshmamma garu. I was attending the Brahma samaj prayers… I stopped puja at home and the holy dip in the river Godavari on special holidays. I did all this only to please my husband but not because I believed in them personally. Now, after nearly sixty years, I am looking back and thinking of those days. I know now that I do not have to be ashamed of it. I am saying this only to point out the hold the traditional values had on us during that period. I heard that saint Ramanujacharya’s wife also had similar experience. She also was not sympathetic to her husband’s progressive views. That story made me think of my past, and convince myself that there is nothing to be ashamed of. I am only sorry, not ashamed. … I could not step outside past the front door in those days. Now I am running this Andhra Mahila Gana Sabha [music society of Telugu women]. I owe it to the incessant teachings of Veeresalingam garu.”

Women in those days took upon themselves to find viable solutions when they met with hurdles. The art of “give and take” was and has been the spirit and character of Telugu women. This spirit of compromise or conformation rather than confrontation was evident in the women writers of the fifties and sixties as well. Kamakshamma and Suseelamma reaffirm the evolutionary nature of social values. Change does not happen in one quick move but takes place gradually, almost imperceptibly.

Newspapers and Magazines

By nineteen-thirties, the Women’s Education Movement gained momentum. The Nationalist Movement needed educated woman. The national leaders found women to be of valuable asset not only for their strength but also in terms of numbers. A little later, Ayyanki Venkataramanayya started Library Movement with educating women as one of its primary goals.

Male activists started magazines exclusively for women and invited them to write and publish. They encouraged women to participate in running the magazines as well.

Veeresalingam started the first magazine Sati Hitabodhini exclusively for women in 1883. It ran only for four years though. Telugu Janana was started in 1884 in Rajahmundry, a city known for its rich cultural history. Hindusundari, yet another magazine exclusively for women, was started by S. Sitaramayya in 1902.

Potturi Venkateswara Rao quoted the mission statement of the editor of Hindusundari as follows [translation mine]:

Considering that [Telugu Janana] is the only magazine currently available for women, and there is no other to compete with, I decided to start this [Hindusundari]. … I hope to educate women, and encourage them to express themselves freely and without fear. I contacted our sisters who have been sending their articles to my other magazine, Desopakari. They all expressed great enthusiasm at the prospect, and promised to help me to make it useful for all women. Some of them offered to write and publish themselves while a few expressed concerns. For fear of ridicule by their female cohorts, some of them preferred to use pseudonyms … We tried to make them take up writing and running the magazine themselves, but the country has not reached that level yet, I suppose.

Further, Venkateswara Rao added:

This rather long editorial is indicative of women’s interest in writing and of their fear of being ridiculed by their female friends, the determination of the publishers and the magazine editors to promote women’s education and to encourage women to act as magazine editors. At the request of the editor, two women, Mosalikanti Rambayamma and Vempati Santhabayamma became editors. In all possibility, these two women were the first female journalists and magazine editors. Approximately, after seven or eight years, Madabhushi Chudamma and Kallepalli Venkataramanamma took the editorial responsibilities of the magazine. It was about this time that the term sampadakulu [Telugu term for male editors] came into vogue, and the two women coined the phrase sampaadakuraandru [female editors] for themselves.

The first issue of Hindusundari included articles on duties of wives [pativratadharmam], tenets for married women, skills required in the performance of their daily chores, women’s songs, articles on cosmetics, hygiene, biographies of foreign women, and leisure fiction. The stories dealing with women’s education and literary interest were given priority.

Evidently, women were invited to participate in running the magazine and women responded zealously. Interestingly enough, they also had expressed concerns of ridicule from their female cohorts! [Italics mine] and considered using pseudonyms. Whether they had actually used pseudonyms is not clear.

The views on women’s education expressed in Hindusundari were the same as those of Veeresalingam.

In the thirties, women had taken the first step towards running magazines not only exclusively for women but also for all readers. Tirumala Ramachandra (1913-2001) quoted Rachamallu Satyavatidevi as the first female editor of a magazine, Telugu Talli, which was not for-women-only magazine. It was published from 1938 until 1944. He also mentioned a female essayist Jnanamba in his book. Ramacandra quoted one full page from one of her articles [non-fiction] as an example of women’s talent. The article was about the delicious nature of Sitaphalam [winter apple] and its health benefits. Lakshmana Reddy noted that Potham Janakamma was the first female essayist. She published her article, “Videsi Yatra” [foreign travel] in 1874 in Andhra Bhasha Sanjivani. Considering the magazine was in general against women’s education, the article’s appearance in the same is significant. It highlights the complex nature of the views expressed and upheld by individuals at any given moment.

- N. Kesari, a nationalist leader, noted philanthropist and journalist, started Gruhalakshmi in 1928 providing a viable platform for women to express themselves. Kesari’s mission was to “improve the health and welfare of women.”

Venkateswara Rao commented:

Although this magazine was intended for women only, it was publishing highly informative articles useful and interesting for all readers. There were several articles of lasting value … Gruhalakshmi provided a platform for several women writers, for women’s education, women’s rights, and encouraged women to work on the spinning wheel at home. It encouraged women to conduct conferences, seminars, etc. and published the news in its pages. In this magazine, the national activist Gummididala Durgabai [Durgabai Deshmukh] published her serial novel, Lakshmi. The story was about an orphan named Lakshmi who survived numerous hardships and later became a teacher. At the end of the novel, Durgabai addressed the readers and said, “if just one had learned something from this story and improved her life, I will consider myself blessed.”

Gruhalakshmi had a special place not only among women’s magazines but also among all the magazines of that epoch.

In the same context, Lakshmana Reddy observed that, “Several women, who had no knowledge of even the alphabet, worked hard to improve their reading skills and became reputable scholars eventually. … Kanuparti Varalakshmamma ran a column entitled ‘Sarada lekhalu’ [letters from Sarada] in which she discussed important women’s issues like Sarda Act [Government Act prohibiting child marriages].

In addition, Kesari instituted an annual award Swarnakankanam (gold bracelet) to honor female writers of excellence. To this day, it is considered one of the most prestigious awards.

During this period, a few women participated in the women’s reform movement. Not all women however subscribed to Veeresalingam’s views. In fact, this is one more peculiarity of our culture, which continued to surface in the women’s fiction in the fifties and sixties. The women’s movement had supporters among men as well as women. In other words, the movement was not one of men versus women, but one of two distinct groups, each comprised of men and women.

Among the women who appreciated women’s education started by Veeresalingam but not all of his convictions, Pulugurta Lakshmi Narasamamba stood foremost. She was a regular contributor to Gruhalakshmi. In 1904, she started her own magazine, Savitri, “challenging Veeresalingam’s position on widow remarriage and declaring war on his other movements as well. Although she opposed widow remarriage, she was a great advocate of women’s education, nevertheless.”

In the thirties, women with minimal education improved their skills and started writing and publishing. In this context, I must mention one book for its historical significance in women’s writing, although it did not fall under the category of fiction. A book entitled Chandohamsi [Study of meter] written by Burra Kamaladevi (1908-1976), who was self-educated was accepted as a scholarly work and prescribed as a textbook for post-graduates in Telugu Literature and Bashapraveena Diploma [attestation of scholarship in Telugu language studies] in schools. That is a validation of scholarship acquired outside educational institutions.

By the end of forties, the literary scene included publication of poetry and fiction by women writers in all magazines. Men openly encouraged women to write. Some male family members went even so far as to write and publish in the names of their wives and sisters but there still was a notable distinction. The women writers of this period stayed within the norms set by society in terms of language and themes. That probably helped them to publish since they gave no cause for concern. This situation however changed immediately after India had achieved independence in 1947.

*****

(Contd..)

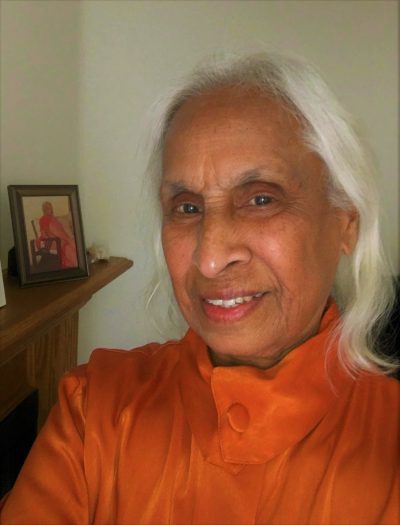

Nidadavolu Malathi born in 1937 to progressive parents, Nidadavolu Jagannatha Rao garu and Seshamma garu. She has Masters’ degrees in English Language and Literature, and in Library and Information Sciences. She has been writing fiction in Telugu since early 1950’s.

She moved to America in 1973. In 2001, she created a website, www.thulika.net, with a goal to introduce Telugu culture and customs through translations of stories and original essays on various topics. She has translated over 100 stories and wrote several critical essays. The website has been a good source for researchers in several universities abroad. In 2009, she started her blog, Telugu Thulika (www.tethulika.wordpress.com) where she has been publishing her Telugu stories, essays and poetry.

Her translations have been published in 2 anthogies, From my Front Porch (Sahitya Academy), and Penscape (Lekhini, Hyderabad). Her short stories in Telugu are published in 2 anthologies, Nijaanikee Feminijaanikee Madhya (BSR Publications) and Kathala Attayya garu (Visalandhra). She also has published eBooks: Eminent Telugu Scholars and other Essays (Non-fiction), All I Want Was to Read, My Litttle Friend (Short Stories.)