Telugu Women writers-4

-Nidadvolu Malathi

Recognition and Reward

Next to publishing, the second shift from the past was in the area of recognition and reward for writings by women. Attempting to put these two issues in the social context of Andhra Pradesh is a complex task. The complexities arise from the multi-layered familial relationships as well as the caste-oriented social hierarchy.

Let’s first examine the question of recognition. Historically, women writers followed the protocol of the upper classes and thus recognition and reward were not a concern for them. Several biographies in Lakshmikantamma’s Andhra Kavayitrulu included comments on the extraordinary talent of the authors but there was very little reference to the reception by the public. This custom of not seeking recognition was evident even in the sixties, to a lesser degree though, as will be shown in latter chapters.

For the moment, I would like to discuss a couple of stories regarding Molla’s status as a poet.

We know very little about the actual environment in which Molla grew up. There is no clear evidence to show how she had acquired the interest and her talent. Generally, the upper class women in the past would not appear in public but Molla did. She went to the court of Pratapasimha, according to the account given in Pratapacaritra [Biography of Pratapasimha] by Ekamranatha, an early historian [translation mine].

Molla offered to dedicate her work to king Prataparudra [Pratapasimha]. The Brahmin scholars present in the court objected to her poetry as sudrakavitvam [work by a lower class person]. … The king, being a scholar and appreciative of her talent, but afraid of offending the court poets, rewarded her appropriately and sent her to the queen’s palace.

I have several questions about this story. What were the circumstances that encouraged her to go to the court? Secondly, how could a lower caste woman gain access to the court? How did she obtain permission to sing her Ramayana epic in the court? The argument that she went to the court to challenge the Brahmin scholars, as put forth by Nabaneetha dev Sen, is not convincing to me. If Molla had gone to the court to challenge the Brahmin scholars, why would she offer to dedicate her work to the king, which imply seeking his approval of her poetry? Why would she allow herself to be escorted to the queen’s palace? Would that not be offensive to a poet, who was determined to prove her talent to the court poets?

A second story about Molla also is interesting not for the questionable details but for the several interpretations it opens up to. Both Lakshmikantamma and Arudra made only brief references to the story in their books. The story was:

One day, Molla was returning home carrying a chicken and a puppy in her arms. Tenali Ramakrishna, a contemporary poet known for pulling pranks on fellow writers, saw her and, as was his custom, saw an opportunity to make fun of her. He asked Molla if she would let him have the chicken or the puppy for a rupee. The question was a double entendre. At one level, it was a simple question—-whether she would sell the chicken or puppy to him for a rupee; and, on another level, an obscenity.

Molla understood the twist and gave him a reply, which was also a double entendre, matching his wits. Her response at one level meant that she would not sell anything to him at any cost; and, on another level, ‘Whatever your intentions are, you know I am like a mother to you’. The story continues to state that, thenceforth Ramakrishna treated her with respect appropriate for mother.

The story raises several questions concerning the status of women in society in general and of women poets in particular. Is this a story of humiliation or success? Does this mean that women poets were subjected to ridicule? Or is it intended to show that women equaled men in a battle of wits? Ramakrishna was known to have played practical jokes on his male contemporaries as well, and at times, ended up at the receiving end of the joke himself. In that sense, can we assume that he treated Molla the same way he would any other poet, irrespective of gender?

I quoted this story to point out a cultural trait peculiar to Telugu literature. In Telugu literature, there is a genre called tittu kavitvam [poetry of slander]. For centuries, it has been a common practice for Telugu writers, especially male writers, to deride each other. Personal attacks and defamation of character have been national traits for centuries. What is considered an offense in the West is a trivial matter for Telugu people. Comments made by Western writers like “d–d mobs of scribbling women” (Hawthorne) or comparing women’s writing to “a dog walking on his hind legs” (Johnson) are dismissed easily in our culture. This trend of personal attacks is widespread in Andhra Pradesh and continued into the seventies and eighties. It did not however deter Telugu women from writing and publishing as will be shown later.

The second female writer to make history was Muddupalani (1730-1790). To my knowledge, Muddupalani was the first female poet to trigger the gender-specific and caste-oriented discussion in Telugu literature.

Muddupalani was granddaughter of Tanjanayaki, a courtesan in Tanjore court during the Pratapasimha regime (1730-1763). Muddupalani wrote Radhikasantvanam, in which she included detailed descriptions of lovemaking. Relevant to our discussion is the controversy surrounding its publication nearly two centuries later. In 1910, when Bangalore Nagaratnamma, a scholar and poet in her own right, attempted to publish the book, she met with strong opposition. Ironically, both the opposition and banning of the book came from the British government.

Among the Telugu elite, Veeresalingam was one of her harshest critics. He condemned Muddupalani’s amorous descriptions as inappropriate for the public. Arudra recorded the account of Veeresalingam’s objections and Nagaratnamma’s rebuttal as follows:

Veeresalingam commented that several references in the book were disgraceful and inappropriate for women to hear or write about.

Bangalore Nagaratnamma in her rebuttal questioned Veeresalingam’s honesty. She asked, “Do the questions of propriety and embarrassment arise only in the case of women writers, and not men writers? Is he [Veeresalingam] implying that it is not acceptable for this author [Muddupalani] to write about conjugal pleasures and without reservation? Is it because she was a courtesan? Is it acceptable for respectable men to write about them? In that case, my question is, Are the obscenities in this book (of Muddupalani) worse than the obscenities in Vaijayantivilasam, Pantulu garu [Veeresalingam] personally reviewed and approved for publication? And what about the obscenities in his book, Rasikajana Manobhiranjanamu?”

This heated discussion, which was published in magazines in the early twentieth century, is an example that women did not hesitate to rise to the occasion and register their protest when occasion called for it.

Muddupalani’s book, Radhikasantvanam, was eventually published thanks to the efforts of a few liberal-minded male scholars. In their appeal to the government, they stated, “It is unfair to ban the entire book simply because it contained some two dozen objectionable verses.” The ban was not lifted until after the British rule had ended though.

Some of the Andhra elite considered the book worthy of publication and got it published eventually. Yet the stigma persists even in modern times, as is evident from some of the critiques published as late as 2002. Lakshmikantamma paid remarkable tribute to Muddupalani’s poetic excellence and her command of diction, yet added, “With her explicit descriptions of sexual acts, the author made it impossible for scholarly discussion of her work in respectable company”. However, she was quick to defend the writer’s position, “We cannot however blame Muddupalani entirely for this. The country was under military rule at the time. It was a chaotic period.” Another comment posted on the Internet is equally subjective: “She wrote Radhikasantvanam to prove that women can write lust and sex as well as or even better than men! Being a Vesya (concubine or prostitute) it was not difficult for her to write about lust and sex.” [Original in English]. Obviously the tone in this comment is one of disparagement.

I quoted these examples to point out the hazy line between the perceptions of men and women in our culture. Individuals from both genders expressed their views based on their own beliefs, irrespective of gender.

By the turn of the twentieth century, a few female writers like Kommuri Padmavatidevi and Kanuparti Varalakshmamma started writing modern day fiction. Since women participated in the freedom movement along with their fathers, brothers, and husbands, they started expressing their perceptions in their writings, which came naturally to them.

Bhandaru Acchamamba (1874-1905) was the first writer to write short stories. One of her stories, “Strividya” [Women’s Education] was about a woman who could not read or write, was not even motivated to learn to read despite her husband’s encouragement. Later however, after he was jailed as political prisoner, she found a reason to learn to read and write. She wanted to communicate with him. The story highlights a side of human nature that a person needs sufficient motivation and justification to learn a skill, and this is particularly true of women. Needless to mention that Acchamamba herself was not motivated to learn to read, at first, although not under the same circumstances. Another story “Dhana Thrayodasi” (The Lakhmi Puja Day) portrayed a wife, who dissuaded her husband from swerving away from his dharma. She made him realize that stealing from his boss was not ethical, and and thus helped him get back onto his righteous path. This could be one of the earliest stories that promoted women’s role in upholding moral and ethical values.

At the risk of repetition, let me recapture briefly the biographies of the pioneers in women’s fiction.

Kanuparti Varalakshmamma wrote a series of articles under the title, Sarada Lekhalu [Letters by Sarada] in which she discussed several contemporary issues relevant to women, and was acclaimed for her insights. She was the first recipient of the prestigious swarnakankanam award in 1934 and Sahitya Akademi award in 1966.

She participated in the freedom movement, was a follower of Gandhi, and an activist. She instituted a women’s organization and dedicated her life to improving the lot of women. Her first story was published in Anasuya monthly, a women’s magazine, in 1918.

Kommuri Padmavatidevi (1908-1970) was a recipient of the swarnakankanam award in 1956. She was well versed in Telugu, Kannada, and English. She was the first female feature columnist. First she ran a weekly column Pramadavanam and later, Mahila in Anandavani. In addition to writing fiction, she was a celebrated performing artist, also had broadcast several programs for women and children on the All India Radio.

Illindala Saraswatidevi (1918-1998) had a high school diploma and a diploma in journalism; ran a feature column, Vanitaalokam [Women’s World] in Andhra Patrika Weekly. She received the Central Sahitya Akademi award in 1958 and swarnakankanam award in 1964. Her anthology of one hundred stories, swarnakamalaalu, was published in 1981. In her preface to the anthology, she mentioned that she had been writing for a long time, even before she started publishing in 1949, and that Kuruganti Sitaramayya, a famous freedom fighter, encouraged her to submit her stories first to All India Radio for broadcasting, and later, to the literary monthly, Bharati. In addition to the short stories, she had written several novels, plays, essays, biographies; and stories, plays and songs for children.

Utukuri Lakshmikantamma (1917-1997) was a celebrated poet, scholar in Sanskrit and Telugu, and esteemed critic. Her literary activities included organizing the first conference of Telugu Women Writers in 1963 under the auspices of State Government. Her monumental work, Andhra Kavayitrulu) [Telugu Women Poets] won Madras Government Literary award in 1953. It is critically acclaimed in literary circles, and remains a reference tool for researchers to this day. She received swarnakankanam award in 1953.

These accounts are intended to highlight the multi-faceted talent of our women writers in the twentieth century.

Finally, let me note one more movement that played a huge part in the women’s writing in the fifties. It was in the area of language. With numerous experiments in journalism, the medium of communication became an issue in the early twentieth century. Gidugu Rammurti Pantulu (1863-1940) initiated Vyavahaarika Bhasha Vaadam, advocating the use of colloquial Telugu in magazines and newspapers. Although, in the early stages, it was limited to language of the polite society [sishtajana vyavahaarikam], the language as being used today, with several dialectal variations, came to be used in the media only after the declaration of Independence, possibly to attract more readers. One of the aims was to capture the readers with minimal education.

It is in this environment fiction by women writers captured the attention of readers exponentially in the early fifties. Their education level rose from elementary to high school diploma, and then, to college degrees, although not in significant numbers. To put it another way, formal education did not play a significant role either in increasing the number of women writers or readership. Suffice to say that the women writers were successfully creating fiction, and their success lay primarily in two areas: their choice of themes and command of diction.

The women writers of the fifties decade started writing about their life and familial relationships—mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, and neighbors; and then, extended to umpteen other issues that filled their homes. They wrote about these themes in a language that drove the point home in readers’ hearts. It was everyday language we all used in our homes, literally.

To summarize, historically, education was available to women in upper and middle class families. After the declaration of independence, the abolition of zamindaries and princely states, women from the royal/ruling class also became middle class. The new middle class began developing a new set of values, which changed dramatically because of the social and political changes in the country. The perceptions of the female writers changed from Bhakti tradition to patriotism and romanticism in the mid-twentieth century, and later, to the awareness of their identities in the second half of the twentieth century.

Secondly, the controversies surrounding women’s education was not gender-specific. The dissent was between two groups, each group consisting of males and females, rather than two distinctive groups of males and females.

A third distinction was between the academic writing and popular writing, which is a modern concept. With the popularization of the adult and women’s education, the non-scholar readership increased exponentially, and it was responding to the fiction by women writers with great enthusiasm, irrespective of the academic evaluation of the same. It provided an exceptionally large platform for female fiction writers.

By the late seventies, the establishment recognized them as eminent writers and began conferring honorary degrees and awards on them. The women writers also became subjects of study for the master of philosophy degrees and doctoral dissertations at the universities in south India.

In the following chapters, I plan to explore how the women writers of the fifties and sixties carried themselves in literature and in society against this backdrop of complex familial and social web. I hope to identify the traditional values these writers continued to cherish, and note also where they deviated from the beaten path and became pioneers for the women of the future generations.

The familial and social status of women writers and the social conditions had been a contributory factor in the success of the women writers in the fifties and sixties.

*****

(Contd..)

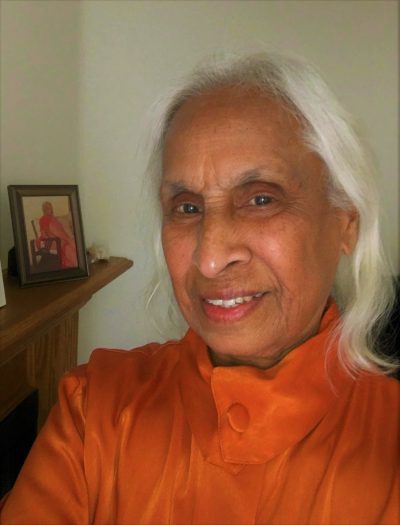

Nidadavolu Malathi born in 1937 to progressive parents, Nidadavolu Jagannatha Rao garu and Seshamma garu. She has Masters’ degrees in English Language and Literature, and in Library and Information Sciences. She has been writing fiction in Telugu since early 1950’s.

She moved to America in 1973. In 2001, she created a website, www.thulika.net, with a goal to introduce Telugu culture and customs through translations of stories and original essays on various topics. She has translated over 100 stories and wrote several critical essays. The website has been a good source for researchers in several universities abroad. In 2009, she started her blog, Telugu Thulika (www.tethulika.wordpress.com) where she has been publishing her Telugu stories, essays and poetry.

Her translations have been published in 2 anthogies, From my Front Porch (Sahitya Academy), and Penscape (Lekhini, Hyderabad). Her short stories in Telugu are published in 2 anthologies, Nijaanikee Feminijaanikee Madhya (BSR Publications) and Kathala Attayya garu (Visalandhra). She also has published eBooks: Eminent Telugu Scholars and other Essays (Non-fiction), All I Want Was to Read, My Litttle Friend (Short Stories.)