Telugu Women writers-5

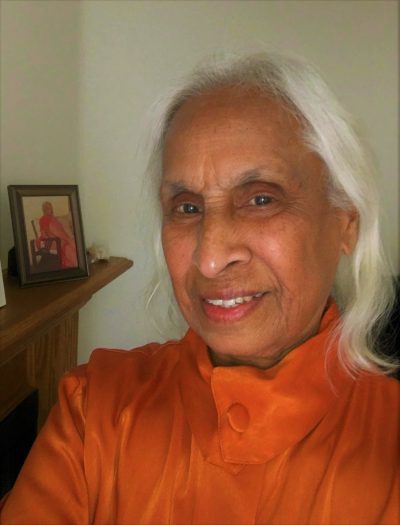

-Nidadvolu Malathi

2.FAMILIAL STATUS and SOCIAL CONDITIONS

In the preceding chapter, I attempted to trace some of the trends regarding women’s education in upper classes and their creative writing, which was mostly poetry. In this chapter, I shall examine the next stage in the evolution of women’s writing—-a spirited mix of tradition and innovation. In some areas, they continued to adopt the practices from the past, and in others, they became dynamic and established their own identity, both at home and in society.

A major shift took place in two areas: In genres, they shifted from poetry to fiction; and with reference to their audience, they moved from private to public, from self to society. Significantly, they kept operating from home, which was a contributory factor in enlisting the family support while expressing their uncharacteristic views, as will be shown later. The women writers of the fifties and sixties still limited themselves to appearing in print only; most of them were not ready to make public appearances.

Women started writing fiction in the second half of the twentieth century. Kalipatnam Rama Rao, an esteemed writer, summarized the history of the women’s fiction in the fifties and sixties as follows:

After achieving independence, the government helped people to open high schools under the newly implemented 5-Year Plan even in small villages in remote corners just for the asking. Formal education for girls was already put in place by then. The girls who had received education up to the fifth or sixth grade advanced to the high school level. By then, the number of high schools in cities also had increased as well. It took seven to eight years to reach this stage.

A second development was in the area of printing. Government loans and investment opportunities played a key role in increasing the number of printing presses. The weekly and monthly magazines started several link magazines [subsidiary organs] in the sixties in order to recover their investment. For instance, Andhra Jyoti weekly started Bala Jyoti for children and Vanita Jyoti for women. With the proliferation of magazines and link magazines, a need to feed them followed. The magazines needed contributors as well as editors. Educated individuals with a sense of social responsibility became editors, which, in turn, produced “social consciousness” writers. That eventually led to competition among the magazines for capturing the largest readership. This spirit of competition forced them, of necessity, to identify and develop a paradigm to attract readers. The focus became not “What is good for the general public” but “What the public wants to read”. That caused a major change in the literary trends of the time.

At this time, women were educated but had not entered the job market yet. Married women stayed at home as housewives while others were waiting for their parents to find bridegrooms with higher qualifications. They were buying and reading the magazines for pastime. Eventually, they started writing about their experiences and aspirations. Some of the women writers, like Ranganayakamma, had already started writing social consciousness fiction.

The educated women felt a need to be recognized as individuals. It was showing in their writings; their yearning to be noticed and understood was apparent in their stories. Oddly enough, they also would accept the woman’s position as charanadasi [Waiting on husband hand and foot]. In other words, they had no clear-cut idea regarding what they wanted. Their views were still in the emerging stage, so to speak. The magazines kept encouraging them, nevertheless.

The third development in the fifties was a change in the social system and the formation of a new leisure class among women. The government plans, the bureaucracy, bribery, etc. helped people to amass wealth. The newly introduced kitchen gadgets created plenty of leisure for women. To make use of their leisure time, women depended on the magazines.

Eventually, women entered the workforce and they continued to read magazines even at work. They would keep these magazines in the desk drawers in the office and read them. The offices were hiring people in large numbers, especially women, since it was a woman’s [Indira Gandhi] regime. Thus, women had no problem in finding the time to read magazines.

Popularity of women writers reached a point where men had to take female pseudonyms to become known as writers. That is my perception, anyway.

A fourth development was in the perceptions of the editors. Normally, they would follow the trends of the readers’ views. Some of the new editors, however, for fear of either competition or their own ignorance, resorted to the most disgraceful crime, which was to ignore the literary values. Both the readers and the editors must take responsibility for this failing.

In response to one of my questions, Rama Rao mentioned that he considers Ranganayakamma, Usha Rani Bhatia, and K. Ramalakshmi as social consciousness writers. Not many women writers are perceptive and/or possess a sense of literary values, he added.

The account sums up the historical perspective of women’s writing during the two decades in question. I will try to elaborate on some of his comments, and discuss other aspects hereunder.

*****

(Contd..)