Telugu Women writers-21

-Nidadvolu Malathi

The novel, Son of the Soil, published in 1972, supposedly depicts the collapse of zamindari families.[1] The rich landowners were losing their hold on the land, urban life was luring villagers to cities, and the old values were changing fast.

Sambayya, who dedicated his entire life to his land, is supposed to be the main character. However, in this novel of 600 pages, a considerable portion, pages 195-496, depicts the glamour of the city and the movie industry. Sambayya shows up a couple of times in this part of the novel but only as a father, not as a farmer. In that sense the title may not be justified. Sambayya himself remained matti manishi (man of soil to the end). However, majority of the readers responded to the depiction of the downside of movie industry. The novel was received very well.

The novel opens with a description of an average day in a farmer’s life and his dreams for his son, Venkatapati, and himself. Several characters are introduced to create an environment of the village politics.

Sambayya works hard to elevate his status. He truly believes that it would be possible if he acquired some land, and married his son into a wealthy family. He accomplishes both—acquiring land and arranging his son’s marriage with the daughter of a local landowner soon enough.

The marriage however turns out to be his biggest mistake. The daughter-in-law, Varudhini, has no intent of moving in with a family below her status. Therefore, she convinces her husband, Venkatapati, to move to the city. After that, the story is not about a crumbling zamindari family anymore. Sambayya is not a zamindar to start with, and Venkatapati never showed any real interest in farming, either before or after his marriage. His lack of interest in farming appears to be due to Sambayya’s parenting.

The most effective elements in this novel are characterization, language, and strangely enough, not the rural but the urban setting. The glamour of the city depicted in the novel is the dominant part that captured readers’ interest.

The story revolves around three characters—Sambayya, Varudhini and Venkatapati. Of the three, Sambayya, a son of the soil, remains true to his calling, stays with farming and finds himself in a position to pass it on to his grandson at the end. He has fought his entire life to keep his land. His downfall comes not from outside but from his own aspiration, his haunting desire to be recognized as a “landowner”.

Sambayya has accomplished his dream, nominally though, by arranging his son’s marriage with a rich landowner’s daughter. Nevertheless, being a son of the soil, he never stops working on the land. Usually landowners hire farmhands but Sambayya, even after acquiring the status of landowner, continues to work on the fields. At the end, he is forced to accept the changing values and he does. He allows his grandson, probably a 10 or 12-year old boy, to make his own decision. This is interesting in itself since he never allowed Venkatapati to make his own decisions, not even at the age of thirty, and certainly not in the matter of his marriage. In that sense, a change in Sambayya’s mode of thinking at the end is implied. Secondly, his grandson Ravi chooses to stay in the village, rejecting an opportunity to receive higher education and enjoy the attractions of city life.

Sambayya’s son, Venkatapati, with no plausible goal in life, has lost everything. He is a farmer’s son but he is no farmer. He has never shown any interest in farming. He is not so much lured by the attractions of the city as by his wife. He is a cardboard character from the start. At first, he is a puppet in his father’s hands, and after his marriage, in his wife’s hands.

Varudhini is a zamindar’s daughter. She is used to a high-class lifestyle and so refuses to move in with the sons of the soil. She is in charge of her destiny. She has no qualms about sleeping with other men in order to get what she wants. Her husband, being a weakling, has no problem with her ways, or anything for that matter. The author is credited with creating an immortal character in Varudhini.

Presumably, readers in the seventies responded to the portrayal of the evils of urbanization and movie industry. This was and has been a huge topic for most of the writers and readers in the post-Independent Andhra Pradesh.

The novel has been translated into 14 languages and also prescribed for non-detailed study in a South Indian university. As stated earlier, for most of the readers the important part has been its readability and the downside of urbanization.

Unlike the social consciousness novels, in the novels of philosophical/reflective and/or ideological themes, the writers’ poignant views dominate the storyline. The writers come out stronger and often as highly critical of the society we live in. Both Lata and Ranganayakamma present their views forcefully on the malignancies that are eating up the contemporary society.

In Kites and Water Bubbles, the institution of prostitution is the protagonist. The novel is a series of agonizing stories and the author’s views on the deplorable state of prostitutes in modern day Andhra Pradesh.

The book opens with a brief description of a brothel house, run by a woman named Rajamma, in the city of Vijayawada located at the heart of Andhra Pradesh. The local police and the pillars of the society are regular customers at the House.

One woman signaled to the other women indicating that a policeman was standing outside window.

“Why fear them? They are also men like any other, aren’t they?” said a second woman.

This is India. In this country, men guard the chastity of women on one hand, and sell the bodies of the same women on the other, smugly stroking their moustaches.

Lata adds her caustic remarks about Rajamma, the matriarch, and her relationship to the girls under her care:

The woman’s name is Rajamma. She has a husband. He claims he is selling soda and paying professional tax. She has two daughters, four nieces [brother’s children] and three sister’s daughters. Some of them lost their mothers and so Rajamma is raising them. A few others lost their fathers and Rajamma’s husband is taking care of them.

Rajamma raising the women makes sense but the next sentence that her husband is “taking care of them” explains their actual status in that house.

The narrator continues to describe the business arrangement with the women under her care:

During the first six months, they [the women] will be allowed to use the first room. The rent is five rupees per night [paid to Rajamma]. Their faces look okay as long as they are using the first room. After one year, they will be moved to the second room. By that time, their faces look worn out and their cheeks sagged. After a year and a half, they will be shifted to the third room. The rent is three quarters of one rupee, darn cheap. By the time they are in the third room, they will have lost their hair and teeth. They will waddle along painfully and with their feet far apart. By the end of the second year, half of them will end up begging on the sidewalk. Half of them will be carrying a child, who will have one horrible red hole for mouth and nose.

Heartrending descriptions like these filled the pages causing middle-class moralists raise eyebrows.

Annapurna, one of the prostitutes, describes how four men subjected her to gang rape, how each one of them took turns and performed sex on her while others cheered on. After listening to the account, Parvati turns pale and asks feebly, “Is that true?” Annapurna continues to describe the satanic pleasures of her customers, and points out the irony in their lives; prostitutes cannot reject customers afflicted with contagious diseases unlike the respectable women in society.

Another woman, Suseela from Madras, points out the ubiquitous nature of prostitutes. Suseela narrates the high class sale of sex in the movie industry in Madras. Strangely, the women in Vijayawada find it fascinating. The author uses the characters only to describe the heinous acts of male customers on them.

Among other characters in the story—Pantulu, who runs a shelter to save destitute women, a hypocritical writer who sleeps with the prostitutes at night and writes about them zealously the next day, and Parvati, who acts in the movies to help the shelter—reaffirm the magnitude of the problem and the miseries of the prostitutes.

The lifespan of prostitutes is short, ten years at best. If they are not dead by then, they are thrown out. They end up on the sidewalk, begging, and suffering the excruciating pains from the diseases they have contracted. None of them can speak clearly, and not one of them will be in good health. Pain and anxiety devour their faces. “Perhaps the world will not let them live in any other way,” says the narrator.

The novel ends with a woman writer, gathering information from the same prostitutes to write a novel by the same name. How the story within the story ends is anybody’s guess. It would appear that the author found herself at a loss for an ending at this point. Does she mean the society is beyond repair?

This story is not a story to which the middle-class readers could relate normally. The book was not officially banned but there was an unwritten taboo in the middle class families at the time. Questions such as “Is it really written by a woman,” “How could a woman know such gory details about prostitution,” and “How could a woman write about them,”[2] were rampant all around.

In response, Lata stated that literature reflects life and “fiction has no sex”. She added that she had learned about their lives because there was a brothel house located round the corner from her house, and she watched the young women suffer.

Lata comes out strong in her criticism of the society with highly charged words. The names of her characters are meant to be sarcastic. Some of the female names she used—Sita, Savitri, and Arundhati—are mythological characters, known for their chastity and devotion to their husbands. Most of the male characters are not given names. They are referred to by their caste or calling. Chettiar is a common name given to male children in the business community. Pantulu refers to a scholar and part of a given name, and kavi means poet. Implicitly the individuals are representative of the social groups.

Lata’s portrayal of the writer as a hypocrite is probably intended to be a call for responsible writing. She uses the writer’s wife to criticize his pretensions in a fiery language. She created the character of Madhavidevi as a genuine and sympathetic writer in contrast.

The protagonist in this novel is not an individual but the institution of prostitution. Presumably, the novel became popular for its shock value. I would argue that a subject of this nature is hard to swallow. Nevertheless that is what it takes to make a point at times. The incidents are truthful, the characters come alive and the total effect, after one has finished reading the book, is one of distress and somberness. The novel is not meant for a reader to skim through the pages over a cup of coffee. Lata made a powerful statement about one evil in the contemporary society and jolted the readers into serious thinking.

For Ranganayakamma caste is evil. In her novel, Balipeetham [Sacrificial Stone], published in 1962, the author illustrates failure of inter-caste marriage, and attributes the failure to some of the irrational beliefs prevalent in the contemporary society.

The story opens with the description of a shelter where the male protagonist, Bhaskar, volunteers. His reason for volunteering originated in an episode he watch in his childhood. He watched a sacrificial lamb being taken to a temple as an offering to the local goddess.

After Bhaskar’s account of his career in volunteering, the story digresses into the story of an old man. This 40-page long narrative has no relevance to the main story.[3] What is relevant for our discussion is the readers’ response to the novel as a whole. This digression did not bother the readers at the time.

The story can easily stand on its own as a separate short story, with all the elements that capture readers’ attention—greed, cheating, illicit relationships, wealth changing hands, retribution for his sins, which resulted in he losing everything and everyone, and remorse at the end.

The novel was originally serialized in Andhraprabha Weekly and was well-received. The weekly installments could have conveyed the same feeling as listening to an oral narrative over several days in a temple courtyard or under a banyan tree.

The conflict between Aruna and Bhaskar arises after Aruna met Bhaskar’s sister and noticed the enormous differences in their habits and language. The class distinction comes into play at this point. The Harijans have their own language and customs that are new or not acceptable to the upper class. Aruna’s uncle and aunt are instrumental in bringing up those underlying, centuries-old values or convictions in Aruna. Matters precipitate after Bhaskar left for a year for his training in Cooperation. Without his presence to remind her of her commitment to their marital vows, Aruna transforms into a different person. Portrayal of this transformation is well done.

Writers often draw their characters from real life. However, there would be/could be major changes once it starts being written. Ranganayakamma mentioned that Bhaskar’s character was based on a story told by a man who claimed it was his friend’s at first, and later, as his own. After several years, the author found out that the man was not as altruistic as he had portrayed himself to be. He had deceived and hurt several women in real life, married two more women, and his exploitation stopped only after his death.[4]

The novel is about inter-caste marriage. The two marriages—that of Bhaskar and Aruna, and Vimala and James—seem to reveal deeper differences than obvious on the surface. Aruna has no problem with Bhaskar’s caste at the outset. Possibly, at first she saw only the obvious in him such as his education, clean clothes, polished language, and clearly internalized norms of the high class society. In that, he is no different from James.

However, after Aruna meets her sister-in-law, she starts seeing the fundamental differences in their lifestyles. In addition, the change in her physical condition, her improved health, may have played a key role. She is not scared of death anymore.

Let us review the family backgrounds first. James is an Anglo-Indian. He is educated and his family has the sophistication on par with the high class society in India. On the other hand, Bhaskar’s family background reflects his lower class roots and their unrefined customs. Aruna is turned away by Sitamma’s “dirty” habits and guileless remarks. To what extent these elements—the lifestyles, the family backgrounds, and social customs—played a role in the success or failure of their marriage? I believe several factors figure into the equation, not just the caste alone.

The expectations, aspirations and the realities of a social reformer are sensibly portrayed. The transformation of Aruna, from a desperate woman with no hope to a woman obsessed with the materialistic pleasures, and to the final acknowledgement of her mistakes, is carried well.

On the lighter side, I must mention the fiction produced by Bhanumati Ramakrishna and Yeddanapudi Sulochana Rani. They have always been received with the same enthusiasm as the social consciousness writers from the start. In a way, they complement and round out the history of fiction by women writers.

Bhanumati Ramakrishna has a unique style. Back in the sixties, she was the only woman writer to present the domestic humor of Telugu families in her short stories regularly. Her most famous work is the creation of a mother-in-law character, a sweet, charming, and traditional woman who is always anxious to help. However, all her well-meaning efforts go awry, and land her and her daughter-in-law in an awkward situation. At the end, all is well that ends well.

In “Kamakshi Katha”, the opening line, “Kamakshi is beautiful, befitting her name” (literally, a woman with longing eyes) indicates that her beauty is the crux of the problem. The male characters are shown as gullible and Kamakshi as playing upon their sympathies. The story reaches the climax when Kamakshi tells them that her husband has contracted a disease and the burden of admitting him in the hospital has fallen on her shoulders. It takes a while for the family to understand that they were swindled of their money. This is a weak point in the story.

The milkman introduced Kamakshi to the family but he does not tell them of his suspicions about her character until after they found out themselves. His comment at the end is:

To tell the truth, Kamakshi and her husband have been playing games and swindling people of their money for quite sometime. They might have collected quite huge amount in this manner. Probably, they are not even married.

If he is aware of Kamakshi’s sleazy dealings, why did he bring her to the family in the first place? Moreover, why did he not warn them in advance? Except for this little lapse, the story reads beautifully. It includes everyday conversations to which readers could relate.

A romance novel is characterized by a specific type of hero, heroine, plot, development and ending. Misunderstandings, mishaps and mildly seductive language are peculiar to the romance fiction. Sulochana Rani’s novels meet these criteria.

In Secretary, Raja Sekharam (Sekharam) is a rich, handsome young man and highly influential in social circles. Jayanti is a young, beautiful middle class woman, looking for a job. Jayanti’s grandmother, the only relative she has, dies in the middle of the story, leaving her at the mercy of this rich and lonely hero.

In the opening episode, Jayanti starts her new job in a local women’s organization. Like all young men and women at the start of their careers, she also hopes to meet people from the upper strata of the society, make contacts and move up. This has a familiar ring for the contemporary readers, especially youth.

The organization, in which Jayanti starts as a secretary, comprises of rich women without concrete goals in life and with their pretensions. It is depicted well. Jayanti’s struggle to maintain her self-esteem and her disillusionment with the activities of the organization are also illustrative of the prevalent notions about women’s organizations. After Jayanti quit her job at the women’s organization, Raja Sekharam offers, first a lift in his car, and later, a job in his home office. After that, all the episodes and the language are deftly crafted appropriate for romance fiction.

In Sulochana Rani’s novels, like in any romance fiction, the language is mildly provocative, which was a cause for concern for traditional Telugu readers. Here are a couple of examples from her novel, Secretary:

Jayanti was upset and decided to jump out of the car. She reached for the door handle.

“Oh, no, no. My God! Stop,” Sekharam’s hand quickly moved and grabbed Jayanti’s hand tightly. For a second their eyes met.

Jayanti’s face turned crimson. Tears welled up in her eyes and were ready to roll down her cheeks any minute.

Sekharam’s fingers tightened involuntarily on Jayanti’s arm. He pulled back his hand quickly and started the engine. The car was moving slowly. The red hue from the winter evening sun was shrouding the world and making every thing look strange.

Another example from the same novel:

“Jayanti!” he shouted, held her arm and pulled her toward himself.

“Ouch.” He felt a slap on his cheek. Both of them moved away quickly. The room was filled with unbearable silence. The breeze coming from outside and the light that filled the room shivered. His eyes were ponderous.

“To keep your mouth shut.” Sekharam pulled her toward himself with all his might.

Jayanti’s palm was about to reach his cheek one more time. Sekharam’s hand seized it and held it tight. His other hand wound around her like steel and stopped her from wiggling out of his grip.

“Pch. I am telling you, leave me alone.” Before she could finish her sentence, his lips sealed hers.

His lips approached hers to stop from but … found something sweet there and stayed there for a long time.

With this unexpected turn of events, Jayanti lost her mind. Her heart went into a shock. She was dumbfounded. By the time she recovered from the shock, she felt as if all the strength in her body was gone. She could hardly stand on her feet. A thin film of haze covered her eyes.

Jayanti was fainting in his arms and Sekharam noticed it.

“Jayanti, Jayanti …” he shouted anxiously.

“I want to sit down,” she managed to speak feebly.

His lips gently touched her lips one more time and then let them go.

Bhagyalakshmi, commenting on romance novels in Telugu, summarized The Thief of Love by Barbara Cartland, in order to point out the strong parallels between Cartland’s novels and Telugu romance fiction as follows:[5]

All the romance novels are identical. It is obvious even from their titles … All these writers give importance to the heroine and walk through the story from her perspective.

The heroine is usually from an ordinary family. She wears clothes, which are simple but enhance her beauty. She is timid, looks naïve and helpless. She meets the hero under strange circumstances, and taken by his looks. Nevertheless, his words and/or actions exasperate her. She tries to stay away from him, and keeps insulting him while getting closer to him by the minute.

The hero is generous, handsome, wealthy, and knowledgeable. He understands her mistakes, anger and frustration. He pampers her as if she is a little child. He stands by her side in times of danger while other beautiful women try to entrap him because of his wealth. Many “Romeos” hang around the heroine and try to get her attention. These secondary characters cause misunderstandings between the hero and the heroine. At the end, they overcome all the obstacles, understand each other and learn that that is the ultimate goal in life.

Bhagyalakshmi further added:

Although there is no literary value in these novels [romance], we cannot ignore them totally.

The writers usually do not pay attention to the development of any other character except the hero and the heroine. … These novels flow like a sweet dream. There is no scholarship. They seem to follow a given formula. They do serve a purpose in terms of providing entertainment though. They provide solace maybe temporary but not unrealistic.

In the present day society, any medium will have its influence on people, especially on youth. It is unrealistic to believe that we can lock them up [the youth] in our homes and shape them according to our own values.

These novels do not cause a mental breakdown. Readers will get tired of them eventually and stop reading them.

Possibly, they may start reading English [romance] novels, which may help them to improve their English language skills.

Two comments in this critique are noteworthy. First, regarding the literary value of romance fiction, I am not sure if it is correct to say that romance fiction has no literary value. The time-honored, Sanskrit epic, Abhijnana Sakuntalam is not any different from modern day romance fiction.

First, let us look at the storyline. The story of Sakuntala is as follows:

King Dushyanta went to the forest on a hunting trip. He saw Sakuntala, daughter of the sage Kanva, fell in love with her and married her on the spot. He gave her the royal signet ring as a mark of his love for her, and returned to the palace. He promised her that he would send a palanquin for her per royal tradition.

Durvasa, another sage, came to visit Kanva’s hermitage. Sakuntala, lost in the thoughts about Dushyanta, did not see Durvasa. The sage was irate and put a curse on her, according to which, the person she was thinking of would forget her. Sakuntala apologized. Durvasa calmed down and granted a remedy; the king would get back his memory of her on seeing the signet ring.

Sakuntala gave birth to a son. Pining for the king, she became skinny and the signet ring slipped off her finger and was lost in the river.

A fish swallowed the ring, and ended up in the royal kitchen. The chef gave the ring to the king, and the king’s memory came back.

The king went to the forest, brought Sakuntala and their son to the palace, and they all lived happily forever.

This brief summary is enough to see its strong parallels to modern day romance fiction. The story was taken from the great epic, Maha Bharatam. In terms of descriptions, characterization, and the development of the story, the analogy is not far-fetched.

During my interview with Sulochana Rani in 1982, I asked her if Denise Robbins and Barbara Cartland were her sources. Sulochana Rani responded that she was in the habit of reading all kinds of fiction; and would not mention any one particular author as her inspiration.[6] It is not unusual for writers to read other writers, and often inspired by those books. As mentioned earlier, Malati Chendur stated she found English magazines Ladies Home Journal useful for her articles.

Bhagyalakshmi’s second comment that these novels may encourage readers to read English novels, and thus help improve their language skills is an interesting perception. Nevertheless, I fail to see how we can hold these parallels against romance fiction in Telugu. Personally, I believe that any fiction that has offered a new perspective for the next generation has withstood the test of time. Is it not part of the definition of literary values?

A brief note on language is appropriate here. Unlike in the west, Telugu writers, male and female, used suggestion and metaphor extensively, following the Sanskrit literary tradition. The descriptions varied from a simple statement like “they were in bed” to long-winding, poetic and descriptive passages. For instance, a love scene in People Ahead of Their Times is not very different from the passages quoted above from Sulochana Rani’s novel.

Indira tried to get closer to Prakasam. Prakasam now understood what was important in life. Indira spoke the truth…. said something … each particle inside of him … helplessness, cowardice and all the desires, which were suppressed till now, woke up inside of him suddenly. The strong desire, which was hiding under his ethics, rose to the surface. Indira saw the redness in his eyes. She turned off the light. It was already past midnight. The winter moonlight was filling the room hazily. In that semi-darkness, Prakasam noticed that Indira’s youth revealed by her white sari and black blouse in minute detail. He pulled her closer. “What are you doing, Prakasam?” she said as she leaned towards him.

Next morning he opened his eyes. The soft Kanakambaram flowers on the bed pricked him gently.

Among women writers, Lata was considered the most bold for describing sexual perversions of men in her novels. She also used only descriptive epithets as opposed to outright profane language.

I must say the women writers of that generation, have used colloquial Telugu exquisitely well. That was one of their strong forte. Readers welcomed it with great enthusiasm but not the academy. Comments like “women writers did not have ease of diction” (made by Kethu Viswanatha Reddy) and “poverty of language in women writers was limitless.” (made by Puranam Subrahmanya Sarma) are, like I said in the case of Molla, remain to be challanged..[7]

Kanuparti Varalakshmamma wrote a story, “The Charm of a Cherished Story” (Katha Etlaa Undale) in 1940s, in the form of a dialogue between a husband and wife. In it, she criticizes harshly the sorry state of affairs in the field of criticism. It is a shame it continues to the present, especially when it comes to criticizing women writers.

In the light of the extraordinary popularity Sulochana Rani and other writers of the fifties and sixties enjoyed, these comments only support my view that the views expressed by the academy and the journalists are biased.

In terms of structure and development of plot, the writers stayed closer to oral tradition. In oral tradition, stories often include several layers, and the narration is not linear but concentric. Thus, from the academic perspective, we do find digression and occasional lapses in the development of plot, imperfection in characterization, and such. However, for the readers of fifties and sixties, and a good part of the seventies, it did not matter since they also grew up in the same oral tradition. The so-called lapses in story-writing technique did not bother the readers. They even appreciated with great fanfare.

At the same time, they have departed from tradition in depicting their characters. Unlike in the past, they were not singing praises of their heroes. Several of the stories portrayed the female characters as strong, sensible and sensitive, and the male characters as weak and dependent on women for support and guidance.

About offering solutions in fiction: Most of the women writers of this period did not proffer solutions, which again has its positive and negative connotations. The one element that caught my attention is the use of death as an ending. There are twenty deaths in the six novels mentioned earlier and that is not counting other deaths that are not crucial to the storyline and therefore not included in the synopses. During the period in question, nearly seven hundred novels and thousands of short stories were published.

From my perspective, the writers saw a problem, created a character and then probably were at a loss to give a closing. Possibly the writers at some point felt a need to bring closure for each character because that was a requirement in modern short story technique, or they thought so. In oral tradition, the stories invariably ended with a happy note.

The fiction of the nineteen-fifties and sixties identified and illustrated the major problems of the period in a manner the readers could relate to. The humor and romance novels provided a different venue and served a different purpose, realistic nonetheless.

In the face of overwhelming industrialization, returning to or rather hanging on to the family values and rural life as depicted in the fiction of this period was a welcome relief for a majority of readers. The diversity in themes and genres opened up a new world for them.

In some ways, the fiction brought the communities together. Readers related to the writers in ways as never before.

5. CULTURE and HUMOR

Cartoons and Jokes

In the preceding chapters, I have noted that most of the women writers came from middle class families and became knowledgeable through reading classics at home. Both at home and in society, they received encouragement in their pursuit of creative writings.

By mid-seventies, the literary scene changed and reflected a blend of diverse attitudes. On one hand, the academy started conferring honorary doctoral degrees on the women writers of the fifties and sixties, and accepted them as subjects for doctoral dissertations and M. Phil. degrees. On the other, jokes and cartoons inundated the magazine pages.

Understanding jokes presupposes knowledge of the cultural nuance. For those who are not familiar with Telugu culture, this chapter may be helpful. In this chapter, I shall review some of the jokes and discuss the cultural background.

I must however admit that not all jokes are funny. At times, the joke is on the joker himself and, at other times, it is simply uncanny. Here is a joke on women writers’ self-aggrandizement:

A publisher: Madam, for some reason, your novel did not sell well this time.

Women writer: Of course, it would not. I told you to print my name on each page and you did not listen![8]

This joke was published in a popular magazine in the early eighties. I went to the library and found that several Telugu books, written both male and female writers and published in the forties and fifties carried the author’s name on each page. Thus, the joke appears to be on the person who authored it.

The following quip was intended to ridicule the ignorance of women writers.

A reader: Did you know that Viswanatha Satyanarayana wrote Veyipadagalu?

Woman writer: I don’t get it. Several people said the same when I said I wrote Veeravalladu. [9]

Implicit in this comment is that the woman writer was claiming authorship of two books, written by the most renowned and prolific writer of the times, Viswanatha Satyanarayana.

Kalipatnam Rama Rao, a highly respected and serious writer, could not resist taking a jab at women writers. In his story, “Kutra” [The Scheme], the narrator describes the nefarious politics and the way the politicians create a mess to confuse the public:

On one hand, the party members were dumping questions in a torrential downpour, and on the other, the press attacked the government like bloodhounds. Talk about editorials, it is like the way “our lady writers writing serials”, the editorials swamped the papers like serial novels.[10]

Fiction by women writers became a common metaphor for excessive production.

- Satyavati, a famous writer, commented that the cartoonists had been depicting women constantly as aggressively. In the past, they had portrayed women holding rolling pins and now holding pens.[11] Apparently, these goals of ridiculing women writers by cartoonists started in the mid-seventies. However, there is no evidence to prove that women quit writing for fear of ridicule. This is one of the areas open for further research.

My position is that humor, as shown in the preceding chapters, is an intrinsic part of our culture, and the cartoons did not stop women from writing and publishing in the sixties and seventies. Some of the writers continue to write to the present.

Cultural Nuance and Familial Bonding

Frivolous jabs apart, a brief note on the cultural peculiarities and humor in our society is relevant to this discussion.

Stories dole out culture in piecemeal. Before looking for generalizations in the larger context, readers need to understand a multitude of variations that permeate a given society. For instance, the custom of arranged marriages is being played out increasingly across the world, and often in a distorted fashion. In reality, there is more to it than presented in modern day fiction.

Let us first examine the extended family set up. In a given household, a family unit is comprised of aged parents, their children and grandchildren. Some times, a daughter or a sister may be moving in with her children also, because of domestic abuse or violence at her in-law’s place. They all take care of each other, commiserate with each other and rejoice in each other’s happiness. A new daughter-in-law becomes an intrinsic part of the husband’s family.

This is the larger context in which each individual acts and reacts in a given situation. One example of this kind of familial bonding for instance is the closeness between Prakasam and Kanakam [sister-in-law] in Transformed Values. The complex love-hate relationship among the family members in The People Ahead of Their Times is a second example of the same underlying principle. They all meddle in each other’s lives simply because they are in each other’s face, to put it bluntly, round the clock. Contiguity is a huge factor in human relationships. Familiarity may breed contempt but it also brings out other emotions like caring and sharing in people. Teasing and name-calling are as much ordinary events as jumping to one’s rescue in times of need.

This spirit of family ties—a labyrinth of familial bonding—is evident in the relational terminology. The relational terminology—the forms of address people use—illuminates the generation level as well as genealogy. Within the same generation, bava is a cross-cousin or sister’s husband; vadina is a female cross-cousin or sister-in-law. Intergenerationally, atta and attamma can be father’s sister or mother’s brother’s wife; atta garu is usually mother-in-law. Sometimes, atta or attamma also may mean mother-in-law. ammamma is mother’s mother and bamma or nayanamma is father’s mother. These relational terms are used as proper nouns in real life as well as fiction. For instance, in “Baamma Rupaayi”, all the characters, except Rama Rao, are referred to only by relational terms: tammudu for younger brother, akkayya for the older sister, chinnakka for the second older sister and bamma for grandmother and so on. Using the relational terms is a technique, which helps to draw readers into the milieu.

Use of relational terms is not limited to members of the family alone. Often it is extended to others such as neighbors, friends and acquaintances as well. One argument is younger people are not supposed to address older people by their given names. Second argument is people feel comfortable enough to forge new relationships without thinking twice about it. Therefore, they improvise an instant relationship and draw on the relational terminology. When two people belonged to the same generation, akka or akkayya (sister) for a woman and anna or annayya for a man are used by the younger of the two. If one of them belonged to an earlier generation, the terms atta, attayya or pinni for women and mama, mamayya or babayya for men are used. Some times, garu is suffixed to the relational term to be more respectful. There is a lot that can be said in this connection, but this is sufficient to understand the affinity of interaction prevalent in the Telugu homes and society.

The same kind of affinity or closeness is evident in the use of professional terminology for proper nouns. People, become friends with their doctors, lawyers and judges, and start addressing them as dactaru [doctor] garu, layaru [lawyer] garu and jadji [judge] garu, forging courtesy and familial values into one term.

The rules of etiquette are evolved evidently from the same proximity of living in real life. We do have some rules about respecting adults, but there is also a free exchange of teasing, name-calling, pulling pranks and making fun of each other. At the end of the day, no offense is intended and none taken.

One good example is the use of second person pronoun for addressing each other between husband and wife. Telugu has two forms of second person pronoun, meeru for formal ‘you’, (which is also plural but not relevant for this discussion), and nuvvu for informal singular. In royal families and a few middle class families, both husband and wife use meeru to address each other. In lower class families and some middle class families, both husband and wife use nuvvu in addressing each other. In the majority of the middle class families, husband uses nuvvu [singular informal] to wife and the wife uses meeru to husband. Although meeru is said to be respectful, this practice however does not prevent two persons from exchanging witticisms, and even an occasional caustic remark or two, thus providing an additional dimension to the humor. Explaining who can say what is beyond the scope of this book. For the present, suffice to say that Telugu stories reveal some of these cultural traits.

In the mother-in-law stories by Bhanumati, the daughter-in-law never talks back to her mother-in-law, never says a word even remotely insulting. In “Attaa kodaleeyam” [A Story of a mother-in-law and a daughter-in-law], the author created a second daughter-in-law, Todikodalu [other daughter-in-law of the same atta garu], to depict that there are also daughters-in-law who banter with Atta garu. The creation of a second daughter-in-law is intended to maintain the integrity of the two original characters, Atta garu and Kodalu, central to the story.

Given below is an excerpt from the story, illustrating the bad blood between Atta garu and Todikodalu, the second daughter-in-law. Humor in the use of the pronoun, meeru, is noteworthy.

“Maybe you are skinny now. Were you not fat when you were a child? Is it not public knowledge?” Atta garu said.

“That is what I am saying too. Maybe you looked like a stick then, but who can miss your big body now? The same people who laughed at me in those days are laughing at you now, are they not?” Todikodalu said.

“Let them laugh. It is my fate that I should take this vulgarity from you.”

“Nobody said anything ma’am. I am the one who is taking all the blame from you. Only you said that my people were poor and dirty. You poured insults on my family. You said my nose is crooked. Only you said my husband has taken to bad ways because of me. You called me garish and wicked.”

In this exchange of words, the two women maintain the protocol regarding the forms of address, meeru and nuvvu. However, the element of respect in the usage of meeru blurred, and it brings up a smile in the readers, who are familiar with our culture and language.

This lengthy explanation is intended to point out that most of our humor is built on such closeness among family members. One needs to keep these peculiarities in mind in order to appreciate the Telugu stories. Probably the best way to describe Andhra humor is to draw on the equivalents from contemporary American humor. The kind of humor that pervades the stand up comedy, celebrity roast and Saturday Night Live in America is an ordinary, everyday event in Andhra homes. Laughter and humor are not separated from life. We laugh at ourselves, at each other, call each other names, and poke fun, all in the name of humor. Self-deprecation is not a negative concept in our culture. At the end of the day, things are not any different for throwing a few punches at each other or oneself.

Humor in Women’s Writings

Very few women writers used humor in their fiction in the sixties.

Bhanumati Ramakrishna stands out for her unique style. She takes ordinary situations and turns them into a comic routine. In her story “Pedda Akaaraalu, Chinna Vikaraalu” [Big People And Small Idiosyncrasies], she makes fun of people’s meaningless fears of small creatures. Here is a brief description of her fear of lizards:

I am afraid of lizards even from childhood days.

Usually, those, who are not afraid of lizards, make fun of those, who are afraid of them. You know the popular proverb, “The cat enjoys while the rat runs for his life!”

I am one of those rats. … Lizard is my enemy for life. I will not walk into a room if there is a lizard on the wall. If I have to, I will ask one of the servants to remove it first, and then slowly enter the room watching every nook and corner to make sure that it is gone. Under unavoidable circumstances, I’ll enter the room furtively, tiptoeing and watching its every move as if I was walking into a lion’s cage. We two—the lizard and I—move around like two meteoroids moving in the opposite directions. No matter how far I am from it, my eyes spot its presence involuntarily. Then my body moves like a robot into the opposite direction.

When I am in a group and chatting, if I see a lizard (usually my eye detects the lizard in a second) I shudder as if it is crawling straight above my head. Then, trying to hide my fear and the bitter taste in my mouth, I say to that person, whoever happens to be closest to the lizard, “there is a lizard above your head”.

I expect that person also to be like me, to be scared and jump to his feet. But no. He does not budge even one half inch. He stays put, looks up and says, “It is just a lizard, poor thing. The most harmless creature.”[12]

Bhanumati’s best creation is the charming character of Atta garu. As opposed to the popular image of an ill-tempered and domineering mother-in-law, her Atta garu is a charming, naive, and traditional woman who is also a busybody. That side of her often lands her in trouble. The narrator, Kodalu, is also traditional in that she is respectful towards her husband and his mother (mother-in-law), and steps in only when her services as a mediator/arbitrator are needed. She comes out as a punching bag, while enjoying a private joke of her own!

To appreciate the humor surrounding the Atta Garu character, the reader has to understand the milieu or cultural nuance. In “Kamakshi Katha“, Atta Garu is assertive. She assures Kamakshi, “Tell him to come here. I will take care of him”, and then backs off as quickly, after learning that he carries a knife with him. Her promise turns out to be an empty boast and for the readers it is amusing.

Sometimes, the cultural nuance is lost in translation, especially, in the descriptions of certain customs. For instance, a practice called madi [touch pollution] is prevalent in South Indian Brahmin families. It may be described roughly as a temporary, quarantine-like environment for a few hours a person creates for herself or himself. She or he takes bath, wears clean clothes, washed and dried the day before, and finishes morning rituals. During that short period, the person remains within a confined area, mostly the kitchen, and avoids all physical contact with other persons and other clothing in the house.

While the madi is a serious matter in Hindu Brahmin families, it is not excluded from the purview of humor. Here is an account of Atta garu eating her meal in a madi environment. The author uses madi to invoke laughter.

As is her wont, my Atta garu sat down to eat from the banana leaf. She is facing the wall with her back to the rest of the world. No ordinary human being in this world is allowed to see what she is eating. The good Lord Narasimha will have to jump out of the wall in front of her to see what she is eating.

That is not all. We cannot even feel the tantalizing aroma of the finely roasted curry leaves. … My Atta Garu will not let that happen. She will make sure that the aroma stayed within the steeled confines of her madi. The only smell she cannot control is from the pickles jar. The smell of her pickles often extends beyond the kitchen walls and into the living room.

On one occasion, my husband sat down with Atta Garu to eat. She moved the pickles jar and the smell filled the entire house like an explosive.

“Huh! What is that stench? Are the oranges spoiled? No. Wait. The stink is awful! Maybe the maid did not clean the area after washing the dishes,” my husband started yelling. Then he turned to me and continued with a grimace, “How come you did not notice it? What are you doing all day, sitting at home? Can you not take care of the cleanliness part, at least?”[13]

I was nearly dead by the time I had finished explaining to him that he was wrong and that was not the case at all.

This passage encompasses humor at several levels. The husband’s banter must be taken contextually. In this instance, the wife does not take his comments seriously; she is not offended. This is obvious for those who are familiar with the author’s style in her stories. For non-native speakers, a brief note may be necessary.

Son comparing the bad smell from his mother’s pickles jar to stinking oranges also is intended to be humorous. Acceptance of this kind of reprimand and the insult as a joke can be appreciated, once again, only when the impact of the demographics is understood. As mentioned earlier, these jokes are comparable to the jokes Americans enjoy at a celebrity roast or watching a stand up comic routine.

The reference to Lord Narasimha is humorous at yet another level. In Hindu mythology, the Lord Narasimha jumps out of a pillar to prove his existence to an agnostic, a demon king, Hiranyakasipa. In the story, the reference is intended to create an image of someone on the floor facing the wall and with her back turned to the rest of the world; and thus, only a person jumping out of the wall in front of her can see her food. Also, implicit is a comment on the extreme attitude of Atta garu in practicing her madi.

This type of humor in the form of punches at personal level found its way into literature in the jokes and cartoons in the late seventies and eighties. Numerous cartoons ridiculing women writers appeared in weekly magazines. Even women writers made use of this type of humor in their stories, rarely though. The cartoons are a comment, not only on the status of women writers, but also vouch for the sense of humor prevalent in our culture.

6. LANGUAGE

Idiom, Nuance, Play upon Words, Imagery and References to Historical Figures or Events

Calling names is offensive in the West except when it is done by a stand up comic or at a celebrity roast.

Bhanumati often uses this technique just to evoke laughter. In “Telivi Thetala Viluva” [The Value of Cleverness], she narrates the congeniality between her husband and his childhood friend, Rao. They both address each other as ‘fool’ constantly. The narrator watches them while they are chatting, and constantly addressing each other as ‘you fool’. She says at the end, “I did not want to interfere between those two fools [italics mine], and so I just stood there, listening to them quietly”. Here Bhanumati picked up the term “fool” from their conversation and used it for a punch line.

In the same story, there is another incident, where the friend’s son-in-law was involved in an accident and ended up on a hospital bed. The narrator learns about the accident while having a casual conversation with Rao.

“I heard that your daughter and son-in-law have returned from America. Will he start a business here?” I asked.

Rao kept laughing as he replied, “At the moment his business is lying in bed in Vijaya Hospital”.

I was shocked.

“What happened?” I asked anxiously.

“Oh, nothing. He had an accident while riding his scooter.”

I became even more nervous. Scooter accident? Is he okay?

Rao continued to laugh. “Oh, nothing serious. Not much anyway, he just broke his arm. That’s all.”

What kind of a person is he? Why is he laughing? Isn’t odd?

“So, where is your daughter?” I asked.

“She is there in the hospital, right next to his bed,” he said, still laughing.

Of course, where else she would be. What a stupid question to ask! When the son-in-law was hurt and lying on a hospital bed, it is stupid on my part to ask where the daughter was. I asked because Rao was laughing while talking about it. I was lost. When such accidents happen it is natural to ask questions and express concern. For Rao, they all meant the same, I guess.

Later in the evening, I told my husband about the accident and he suggested that we both should go to the hospital to visit him. At the hospital again, I watched as Rao and my husband went on ranting and laughing.

I stood there pondering over the mentalities of those two friends.

With the last line, the readers understand that even the narrator thought it was odd. But, by saying several times that the two friends had been laughing at each other’s misfortunes and miseries, the narrator seems to point out that it was their way of dealing with the situation.

Playing upon words is one more way of creating humor. It may or may not get the desired effect in translation. The following example however translated well, I believe.

One woman asks, “Is your husband a bookworm?”

The second woman says, “Oh, no, just a worm.”

In this instance, precise translation is possible because the word ‘bookworm’ has an exact equivalent in Telugu, pustakappurugu.

Telugu writers used English words in Telugu sentences to create humor. The practice started probably in the forties when speaking English became important among the elite. In recent times however English words have become an intrinsic part the narrative technique in Telugu fiction. Sometimes, one third of the words in a story account for English terminology, and it loses its humorous touch.

In general, English is considered the language of the elite and the upper classes. The practice in turn became an effective instrument to make a mockery of such usage. For instance, in the story, “Vishappurugu” [Venomous Creature], the English teacher was anxious to prove his love of his mother tongue, and the Telugu teacher was anxious to prove his English language skills.

“I told you. He is an irresponsible fellow,” the Telugu teacher said in English, shaking his head.

“You must take severe action against him,” the English teacher expressed his valuable opinion in classical Telugu.

Lata used caustic and sarcastic remarks in her writings profusely to make her point and to make the readers laugh. Sometimes it is a simple comment on the idiosyncrasies of a few people:

Among my friends, there was a charming person who never smoked. He used to remind us each time he got an opportunity that cigarettes were bad for one’s health, only bad people smoke, and only he was perfect since he never smoked. Another friend of mine, who got tired of his ranting, worked on him and got him into the habit of smoking. That settled the problem once for all.[14]

Ranganayakamma uses wry humor to drive a point home. She often takes a sharp jab at the dated traditions and dishonesty in people.

In her well-known novel Andhakaramlo (In Darkness), she pokes fun at the man who showers praise on his wife for her chastity and then visits brothel houses at night for sexual gratification. The wife lives under the delusion that her chastity is the most important thing in the world. However, one day she decides to throw it to the winds and goes to a young man who is sleeping on their front porch. The narrator comments, “The young man, unaware of her impeccable chastity and unparalleled devotion to her husband, gave her immense pleasure and had the time of his life himself in the process!”[15]

That is a powerful comment on the subjugation of women in the name of chastity. The caustic remark is sure to bring up a crafty smile and “you know what I mean” look in a Telugu woman.

Ranganayakamma is playful at times. In her story, “Artanaadam” (A Desperate Cry), she describes the grandmother’s impending death in a lighter vein.

Given below is a paragraph describing the grandmother and her grandchildren, who came to visit her, since they were told she was dying. As it turned out, she was not dying after all. Then her grandchildren started to tease her.

“Gosh! Is this a game for you?”

“Our vacation is gone now. Next time we will not come even if you died for real. Be nice. You might as well die now and be done with it,” one of the grandchildren said tauntingly.

“What can I do, kids? Lord Narayana is not yet ready to take me to his home,” she said, smiling with her toothless mouth.

“May be Chitragupta lost your file. Stupid offices. This has become quite common nowadays,” said another grandson, a high rank officer.

“That is not it. Grandma has performed Chitragupta ritual four or five times. Therefore, he is not going to issue orders to take her away anytime soon. Let’s go.”

“Stop it. Don’t talk like that about Grandma. She is so sweet. Don’t you remember she used to give us all cream, behind mom’s back? And the rock candy too,” Radha said.

“Yes of course you will say anything to support her. Did she not have earrings made for you?”

“Grandma! It seems you have a lot of money. Are you going to distribute it to all of us or not? Tell me you are not ready to die anytime soon and I’ll show you my muscle,” one spunky grandchild said.

“Ram! Ram! I have nothing to give, not even a broken shell. Would I lie when I am ready to die?”

“Grandma, first tell us this. Do you really want to die or not?”

“Of course, I want to. Lord Narayana has not sent for me yet. What can I do?”

Good point!

This description has several layers. First, the exchange of witty remarks in an inter-generational context. This is not common but not strange either. In some families, members tease each other freely, irrespective of generational gap.

Second, the reference to a mythological character, Chitragupta. According to Hindu beliefs, Chitragupta is the bookkeeper who keeps a record of the good and bad deeds of individuals and decides who should die when. The Chitragupta ritual is supposed to please him and help individuals to avoid hell after death.

Third, the reference to files disappearing in offices nowadays once again is a jab many readers appreciate. It is so common in Government offices.

Culture-oriented references to historical incidents are common in Telugu fiction. Sometimes a single instance may contain several layers. One such instance is from a short story “Shortchanging Feminism.”

“So, is he a modern day Veeresalingam?” Parvati asked.

Sita smiled vaguely. “Yes and no. There is a small difference, I suppose. Veeresalingam worked to arrange marriages for child widows. And here, this man is fooling around with married women and making their husbands fools.”

In this snide remark, there is a play upon the word “fool”. The Telugu word vedhava means a jerk or an idiot and vidhava means widow. The two words are so close in pronunciation the joke works well in Telugu.

Secondly, there is a controversy regarding the intentions of Veeresalingam in advocating the widow remarriages. While some critics argued that Veeresalingam genuinely believed in promoting widow remarriages, others argued that Veeresalingam in reality was trying to protect naïve young men from being seduced by young widows. While it is a stretch to convey all this in a quip, the simple play upon the word “vedhava” is direct.

Most of the writers did not build humor into the stories in dealing with serious subjects. However, humor is part of our everyday life. And, women writers have made use of this custom, rarely though.

The story, “Fear” by Meera Subrahmanyam, describes one day in the life of a beggar, which turns out to be his last day. Death is a serious subject. Yet the tone in the story is one of sarcasm. It pulls several punches at the government, the mentalities of college students and even the beggar’s wife; referring to her as a pativrata is a euphemism.

The reactions of the passersby to the sight of the corpse are amusing. Comparing the wife’s final round of sobs to the national anthem at the end of a movie is the high watermark in the story. After declaration of independence, the movie theaters started playing national anthem as a mark of respect towards what we had achieved. In reality, nobody cared. People would leave the theater as soon as the song started to play. In both cases, that of playing the national anthem and the display of the dead body, the same lack of respect is implied.

To summarize, the humor and sarcasm are built-in tools in our culture, possibly therapeutic. And it is hard to convey these connotations across cultures. One needs to strain and transpose oneself into the source environment to appreciate it, I believe. It may not be easy but almost a requirement in learning about other cultures.

7. CONCLUSION

The consensus regarding the achievement of women writers during the period, 1950-1975, has been that they popularized fiction and augmented readership. Their achievement, breaking into publishing industry successfully, has never been acknowledged. In fact, there has never been a systematic attempt to study their contribution to the history of fiction comprehensively.

Universities have produced dissertations on individual writers or individual works, based on a given paradigm, using the tools designed by Western scholars. This explains the lukewarm critical works on women’s writing by male scholars in the seventies and eighties. It is even worse that women scholars also follow the same methodologies and draw the same conclusions.

The women writers of the fifties and sixties developed a new form, which did not lend itself to the critical evaluation, based on Western criteria. It would appear that the scholars and the critics chose to ignore the fiction produced by women consciously for reasons only they can explain.

The women writers differed from their predecessors in their choice of genres, themes and technique. They had taken the narrative technique from oral tradition and applied to modern fiction.

For instance, in their stories, the female characters are depicted as shrewd and pragmatic in their approach to life. Some of them are in charge of their destiny. The male characters on the other hand are depicted as dependent on women, as guardians of dated traditions and apprehensive of public opinion. This is a telling departure from the inherited pattern of men’s thoughts and actions, and a marked change in the perceptions of women’s writings.

One of the major criticisms, leveled against the women writers has been that they are lacking in a comprehensive understanding of the system in a larger context. I disagree with this argument. From the writers’ perspective, a family unit is a part of that system and a consequential one. The women writers of the fifties and sixties succeeded in portraying that part of the system in bold relief. That contributed immensely to the greater good in its multifarious forms.

The women writers of this era were quiet and unassuming in real life, cherished traditional values, while registering their dissent in their fiction. As shown in chapters 4 and 5, they noted distinctively their perceptions of human nature, interpersonal relationships, and innumerable complexities at home and in the society. What is interpreted as confusion by scholars is in reality the writers’ shrewdness. It is an innovative way of synthesizing the accepted norms with the radical changes taking place in the lives of women in the new world.

Another aspect that became clear to me in this study, and needs further research, is the myths about women writers. Ordinarily, each generation draws on the contemporary beliefs and customs, makes up their stories, and creates new myths in the process.

One good example is the story of Molla. Several unverifiable stories are widespread in print and by word of mouth about the poet. It may not be possible to sift fact from fiction in her case. Additionally, new stories are sure to be written as we go along. When I saw a reference to Molla’s poetry as “slokas”, I could not help wondering if that was one more effort to elevate Molla to a scholarly status. Sloka is a term used to refer to the verses in Sanskrit. Molla wrote Ramayanam in pure Telugu. She had stated explicitly in her prologue that she stayed away from the Sanskrit idiom and practice. In that context, referring to her poetry as slokas is incorrect, I would assume. Similarly, the comment that Molla went to the king’s court to “challenge” male scholars is untenable in my opinion. Challenging and craving to obtain the approval of male scholars is an overlay of modern day views of scholarship on a poet, who evidently did not care for such encomiums. I would be interested to know if there was evidence to prove that the court scene had actually taken place.

In assessing the fiction by women writers of the fifties and sixties, we need to keep in mind that three factors played a significant role in creating their stories. First, our oral tradition, which had a definitive set of rules in narrative technique. Secondly, the women’s literature as an expression of their experiences and their environment from their own perspective. And, third, the society they had created in an environment, in which they could overcome smaller hurdles to achieve higher goals. Battula Kamakshamma is a classic example of what women could achieve by conforming to the traditional values in appearance, while maintaining their dignity and pursuing their goals. It was a ploy, and a clever one. They all had succeeded in bringing about tangible changes in society using the methods available to them.

The fifties and sixties writers walked on a double-edged sword and succeeded in maintaining the traditional family values at home and entering the publishing industry in the public sector. They successfully resolved their problems, both as individuals and as writers, and wrote about the other issues such as human values, family values, personal relationships, physical needs, emotions, among others.

My point is there are several unverifiable stories regarding the writers of the past. But given the facilities we have today, it is possible and important that we undertake a thorough research, gather all the information about the writers of our immediate past and record it for posterity.

It is also important to develop appropriate tools for studying the fiction of this particular period, since it was unique in several ways.

As I stated at the outset, I have fewer answers and several questions. Why the women writers were ignored by the Academy for so long? If their work was really lacking in discernment, why were they accepted as subjects for doctoral dissertations in the later decades? Why honorary doctorates were conferred on them? What caused this shift in the perspective of the scholars in later years? After this shift, why the inclusion of women’s fiction in anthologies and assessment of their fiction in the critical works continues to be nominal?

A brief note on feminism is in order for a couple of reasons. A young feminist writer asked me, “You have had so many experiences in your life. How can you not be sympathetic to the feminist cause?”

Secondly, in the past two decades, I have been labeled first “feminist” and later “anti-feminist”. Therefore, a brief note on my position on feminism would be helpful, I thought.

I believe the label, any label for that matter, constrains the writer’s perspective and renders her views slanted, may even be distorted to some point. It is common knowledge that even greatest scientists, who postulate a particular theory, tend to ignore the arguments or proof contradictory to their postulation.

I am sympathetic to the women who have suffered hardships as well as all the other underdogs, regardless of gender, age, race, or any other criterion. I do not believe that I must court an ideology to be a good writer or a decent human being.

One question that keeps coming back to my mind is why the women writers, who have had tremendous success in the sixties, are courting these labels now. In recent times, some of the fifties and sixties writers have proclaimed to be feminists. Abburi Chaya Devi for instance, gave an account of the proscriptions she had faced from her father during her childhood.[16] There is however one notable distinction, which is the reference, or lack thereof, to her creative writing. She did not state that she was discouraged from writing because she was a woman.

Feminism in America originated as a political organization and writing to promote these ideals has been labeled feminist writing. Later it extended to fiction promoting that ideology.

In Andhra Pradesh, it appears to be slightly different. There is however one caveat. I have been living far away from the Telugu country for a very considerably long time. So, my perception may not be correct. However, to the extent I have noticed, feminism in Andhra Pradesh came to be writing exclusively women’s heartrending stories in our society and blaming it entirely on the male population, or patriarchy to be specific. This kind of lopsided perception hurts creativity. Additionally, it sounds hollow when the same women are able to enlist support from men in promoting their writing activities.

I must add that all the writers who claim to be feminist are not writing in the manner. I have feminist friends who are writing well-developed stories. My point is, I do not want to give an opportunity to our high-brow scholars to misrepresent my standing as a writer and misconstrue my stories into which they are not. My stories are meant to be creative writing, not promote an ideology.

I must further elaborate on the creative technique, which is instrumental in appealing to the widest range of readership. As shown in chapter 4 on their craftsmanship, for a vast majority of readers, the issues and characters portrayed in the stories are the most important aspects in a story. The stories, written to promote a particular ideology, tend to portray monolithic characters either as victims or abusers. In other words, the writers run the risk of creating unrealistic, asymmetrical characters, which fails to convince a vast majority of readers. Further, the ideologists tend to sermonize, which again fails to appeal to a vast majority of readers. In our daily lives, we see people far more complex than presented in stories promoting a single ideology.

Men in Andhra Pradesh have supported women’s writing in the past. However, starting late nineteenth century, the support has acquired a new hue. While Veeresalingam started women’s education movement, his position is far from what we understand by the term women’s education. He held the view that ‘a woman’s duty is to support her husband’. There was no ambiguity in his statement. Today’s feminism certainly could have no place in his “education for women.” He would not want women to be doctors, lawyers, and engineers. Strangely, most of today’s feminists praise Veeresalingam as a promoter of women’s education.

Similarly, in current day society, we find rejection of women’s creativity in the criticisms of male scholars and prominent journalists. The irony is if a female writer happens to be a daughter or wife of a famous male writer, the same scholars would pour praise on her writings, and even offer to translate into English. In my opinion, comments like “women writers set the clock back to 50 years” or “they don’t even have ease of diction” are unfounded, if not disingenuous. My question to them would be what provokes them into making such comments without proof.

My point is feminism in Andhra Pradesh is bungled. Each of them has his/her own definition. In that, personally, I would rather not be labeled.

I believe that the world is ridden with problems that go far beyond women’s issues. In that, I can safely state that I am still hanging on to the traditional values. In my mind, traditional, human values do include integrity and self-esteem, which I cherish dearly.

Those, who have read my stories, will know that I have dealt with a wide variety subjects, not just women’s issues exclusively. To me, most of the problems are arising out of modern day self-absorption of individuals in the name of “success” and “achievement”. In the past, people cared about others. Now the driving force is to care about oneself, to the exclusion of all others.

In short, label is an academic feature in literary circles. The women writers in the past did not follow the academy. During that period, they were proud to be who they were. Some of them are now taking these labels, maybe they started feeling insecure, or, they wanted to assimilate into today’s literary world, which has turned out to be a business. These views of mine are open to debate, I admit.

It is my sincere hope that the current and future research scholars undertake a thorough study of this subject and throw some light on the history of Telugu fiction.

*****

(The End)

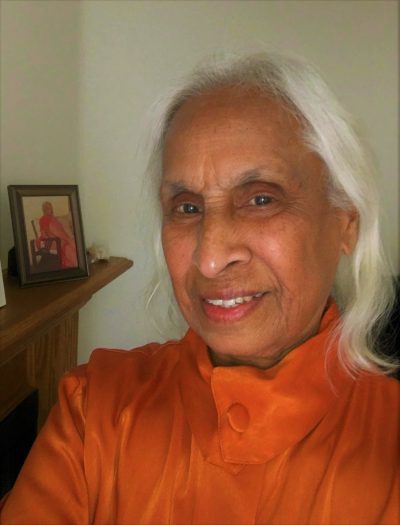

Nidadavolu Malathi born in 1937 to progressive parents, Nidadavolu Jagannatha Rao garu and Seshamma garu. She has Masters’ degrees in English Language and Literature, and in Library and Information Sciences. She has been writing fiction in Telugu since early 1950’s.

She moved to America in 1973. In 2001, she created a website, www.thulika.net, with a goal to introduce Telugu culture and customs through translations of stories and original essays on various topics. She has translated over 100 stories and wrote several critical essays. The website has been a good source for researchers in several universities abroad. In 2009, she started her blog, Telugu Thulika (www.tethulika.wordpress.com) where she has been publishing her Telugu stories, essays and poetry.

Her translations have been published in 2 anthogies, From my Front Porch (Sahitya Academy), and Penscape (Lekhini, Hyderabad). Her short stories in Telugu are published in 2 anthologies, Nijaanikee Feminijaanikee Madhya (BSR Publications) and Kathala Attayya garu (Visalandhra). She also has published eBooks: Eminent Telugu Scholars and other Essays (Non-fiction), All I Want Was to Read, My Litttle Friend (Short Stories.)