Telugu Women writers-2

1950-1975, Andhra Pradesh, India

(An Analytical Study of Historical, Familial and Social Conditions that contributed to women writers’ phenomenal success immediately after declaration of Independence.)

-Nidadvolu Malathi

PUTTING AN END TO THE BOILERPLATE LITERARY HISTORY

Foreword By Kalpana Rentala

We have one thousand years of literary history. Up until now, there has been an effort to portray women’s literature only as a part of the mainstream history. Women writers were mentioned only sporadically, one Molla or one Timmakka. Our history is a male-dominated record that has been accustomed to record women’s participation only as a measly strand.

Ever since westernization started influencing our culture, women’s awareness started changing. That is reflected in the fields of literature, science, and sociology. The massive changes, which were taking place in the men’s perceptions, have been noticed but there has never been a systematic attempt to note the changes that were taking place in the perceptions of women, the mode of development in their participation in the academy, and their mode of thinking.

Today, a concrete attempt to question this boilerplate documentation, and rewrite a different kind history has begun. This is not limited to a handful of persons or books. They are examining the women’s consciousness from several angles and in various fields. Until now, women’s contribution has been recognized only partially, and limiting to a few writers or a specific period. A few responsible writers however departed from this tradition in an attempt to study women’s writings in a larger context. Nidadavolu Malathi is one of them.

In this book, Malathi examines the history of Telugu women’s fiction from a completely different perspective and from existing records.

In general, whenever women’s fiction is mentioned, the writers presented are invariably either a few novelists or feminists as they came to be known in the 1980s. But, there never has been a better, comprehensive discussion on the subject. The number of female short story writers was much higher during the time the freedom movement and the women’s education movement peaked, but it was not so after the declaration of independence.

This is particularly obvious, when we consider the availability of printing presses, women’s awareness of identity, and several other amenities available for women to write. The number however was much less, comparatively speaking. A famous critic, Rachapalem Chandrasekhara Reddy raised the question, “Should we attribute this decline in the number of female writers writing short fiction to their preference to write novels instead?” (Telugu Kathakulu – Kathanareetulu, part 3, p. 111).

Contradicting that stance, Malathi has shown, quoting several examples, that women writers have not written only novels but also several excellent stories. She has also discussed at length their themes and technique. Malathi’s detailed analysis of their themes and technique in this book can be considered a milestone in the literary history of Telugu women’s writing.

Malathi did not use the term “feminism” yet she has pointed out specifically that women’s awareness of identity did not start with the feminists in the eighties. It was evident even in the fiction of nineteen fifties. Her detailed analysis of stories like “Eduru Chusina Muhurtam” by P. Saraladevi, depicting women’s awareness of identity enhances our respect for writers of the past.

The history of Telugu fiction, which often quotes Diddubaatu by Gurajada Appa Rao as the first short story in Telugu giving very little importance to women’s writing. The histories speak extensively Gurajada, Malladi, and Sripada, and very little about Bhandaru Acchamamba, Kanuparti Varalakshmamma, Kommuri Padmavati, Illindala Saraswatidevi, P. Sridevi. Adimadhyam Ramanamma, Sivaraju Subbalakshmi and several others. Nobody discussed the works by these women writers.

As far as the discussion on the fifties writings is concerned, reference to women’s writings appears naamke vaaste [nominal]. If we see the books and articles written so far on Telugu short story, we find only one or two unqualified sentences limited to three or four women writers and one all-inclusive phrase “and others”. We have no evidence of anybody paying serious attention to these women’s stories, their themes, and techniques; much less analyzing them in detail. On rare occasions, we might find a complete article on women writers. But nowhere have we seen a complete analysis of women writers’ contribution as a part of mainstream literary history. I have no doubt that Gurajada, Malladi and Sripada are great writers. But, my question is, don’t we have to study the women’s fiction in detail and in the same light in order to assess their works, and see how they stack up?

When we examine the story, “Diddubatu” by Gurajada in juxtaposition with the stories, “Strividya” and “Khanna”, written by Bhandaru Acchamamba, we can understand that the latter two stories are in no way inferior to Gurajada’s story. Acchamamba, who was already educated by 1900, had written women’s biographies and several stories, yet her writings were ignored. No literary historian of Telugu fiction bothered to make a note of Acchamamba’s stories.

One of her stories, “Khana”, for instance, narrates the social conditions of her time and her ill-fated life. Khana was wife of Mihira, an astrologer in king Vikramaditya’s court. The story vouches for the women’s awareness of their conditions as early as the 1900s.

Yet another example is the story “Kuteera Lakshmi“ by Kanuparti Varalakshmamma.The story depicts the aftermath of the Great War, the manner in which the large-scale industries such as the Manchester Company caused the ruination of the local and handloom industries, and the significance of our nationalist movement. Once again, very few literary historians made a note of this story. It sounds harsh but the reality is throughout the history from the earliest to date, the literary historians stated women’s writings as “by women and for women only” but made no serious attempt to give it its due place in history and examine it as an intrinsic part of the mainstream literature.

Women have always been perceived as a part of our movements—women’s, social conditions and education—but there is no other attempt to place them contextually. History made a special note of women’s education only for the purpose of women’s role at home, for their contribution to the family’s well-being, but not for assimilating them into the mainstream. The social reformers intended women’s education only to make her a better housewife. There is no evidence to show that they wanted women to become better persons. Malathi pointed out this biased view of the reformers in her book.

The period immediately following the achievement of independence, namely 1950-1975, was a very important period. That was the time when major changes were taking place in all the fields—political, sociological, and literary. And most of the literary historians dismissed that significant period, labeling it the age of novels or romance fiction.

During that period, several significant novels were written. Several novels illustrated sensitive issues relating to man-woman relationships, and important familial issues. Yet, even a senior critic like Puranam Subrahmanya Sarma’s comment on this fiction look questionable. In his article, “Telugu Katha, Samaajika Spruha” [Telugu Story And Social Consciousness], he wrote, “Many women writers were able to depict a woman’s life to the extent it was correlated to a man’s life. However, one can see from their writings that women knew absolutely nothing about the man’s world. There is no brainpower. They are hopelessly poor in their command of language. They do not read at all. They are lifeless cutouts submerged in self-aggrandizement, slandering others, and ego trips. This confounding state, which the women had created, pulled down the level of Telugu readers, and turned the clock back to fifty-years.” (Telugu Katha: Vimarsanatmaka Vyasa Samputi). Strangely, the same Subrahmanya Sarma registered his protest in 1976, when Andhra Pradesh Sahitya Akademi eliminated the fiction category from their list of various genres for presenting awards.

On the same lines, a famous fiction writer and notable critic, Kethu Viswanatha Reddy commented, “Women writers did not care about short story as much as novels. … Even writers like Sridevi, Saraladevi, Turaga Janakirani, Kalyanasundari Jagannath, Vasireddy Sitadevi, Acanta Sarada Devi, Pavani Nirmala Prabhavati, Nidadavolu Malathi, and Ranganayakamma, have not developed any notable technique in short story writing. The reason is women are still lagging behind in their perception of the modern day consciousness. And what is even worse misfortune is there was no ease of language either. [Bhashaa Saaralyam Kudaa Ledu].” (Viswanatha Reddy. Drushti, p. 73).

These few examples would suffice to show how the criticism in the field of Telugu fiction has been changing, based on the perceptions of individuals in various periods. Up until now, Telugu people have gotten used to seeing only this kind of literary criticism, which is subjective.

Malathi’s book, for a change, takes up a significant part of the contributions made by Telugu women in the field of fiction for a period of twenty-five years and presents it from a refreshingly new angle. Malathi, positioning them in their social and historical context, analyzed the themes, genres and their technique effectively.

I have no doubt that this book will be a valuable contribution to the true history of Telugu literature.

Kalpana Rentala

Writer

September 27, 2004

Madison, Wisconsin

*****

2

Bhaskaracharya(11th century), a notable mathematician, taught his daughter Leelavati mathematics. Leelavati authored a textbook, Leelavati Ganitamu, which is acclaimed as a valuable contribution in the field of mathematics to this day. I must however mention a variant of this story. There is also a contention that Leelavati was not his daughter but wife, and that Bhaskaracharya himself wrote the treatise and named it after her.

Regarding the story of Leelavati and other similar stories to follow, we need to ask ourselves why or how they had come into existence in the first place. Let me recount a couple more stories first and then address the questions.

The story of Mohanangi (16th century) is about father-daughter relationship; specifically, father encouraging daughter to write an epic. According to the story, Mohanangi was daughter of Emperor Krishnadevarayalu. Lakshmikantamma narrated the story in her book, Andhra Kavayitrulu as follows. The original text was in Telugu (translation mine).

One day Krishnadevarayalu went to his daughter’s mansion and noticed that she was lost in thought. He asked her,

You, with knotted eyebrows, seem deeply disturbed,

What might be troubling you, dear child?

Mohanangi replied,

Father, I am contemplating not a few silly lines,

I know not what you might think,

But I am hoping to write an epic,

Much to the chagrin of those who ridicule female writing, and, ask why women write?

Why not stay in the kitchen and do chores.

Krishnadevarayalu replied,

Do let me have the pleasure of your delightful poetry.

Until now, you turned a deaf ear to my pleas,

You have been indifferent. …

In knowledge, you are no other than Goddess Saraswati,

Your talent excels not only other women,

But also the male writers, who boast of their talent.

Some foolishly may look down on women,

But is it not common knowledge that

Great female scholars existed in the past?

When I came across this passage, my first thought was to take it as an indication of the existence of female scholarship in royal families and male family members support of women’s writing at the time. Later, however, I learned that my assumption was incorrect. Two learned scholars, Nayani Krishnakumari and Kolavennu Malayavasini, have stated that there was no supported documentation for this story. Malayavasini added that she was not questioning the scholarship of Lakshmikantamma but would like to set the record straight.

In my mind, this new information raised a few other questions: Who made up this story? When? And under what circumstances? Is it possible that a father or a daughter narrated his or her own experience and put it in royal context, in an attempt to earn credibility to the story? Why would one refer to ‘the ridicule of female writing’ or ‘great female scholars of the past’, if such perceptions were not prevalent at the time?

A second female writer I would like to discuss is Atukuri Molla. The stories surrounding her life and times are interesting. Lakshmikantamma stated Molla’s time it to be 1320-1400 (or 1405); and Arudra determined that Molla belonged to the 16th century. Once again, I would not consider this discrepancy as gender-related. Telugu history is full of such unverifiable dates concerning writers, both male and female.

Atukuri Molla, also known as Kummari Molla, belonged to potters’ caste. She was a respected scholar. Molla and her father espoused Vira Saivism and defied the social norms of traditional Brahmins. She decided to pursue her literary activities and remained unmarried for the same reason, in defiance of Brahminical traditions.

Molla’s major work, known as Molla Ramayanam, was written in unpretentious Telugu. The book is highly admired for its native idiom and cultural nuance, unadulterated with long winding and heavy Sanskrit phraseology. She was the second female poet to write in pure Telugu. Arudra made a special note that, “Molla Ramayanam enjoys popularity even to this day while several other Ramayanams by esteemed male scholars of her times were lost in the folds of history.”

In the modern period, we have better documented evidence of men supporting women’s education. The story of Bhandaru Acchamamba (1874-1904) is a case in point. In fact, her story registers both the views for and against female education within the same family. Her younger brother, Komarraju Lakshmana Rao, a famous activist and respected journalist, encouraged her to learn to read. At the same time, other members of her family were opposed to the idea. Acchamamba was indifferent to her brother’s pleas at first but later changed her mind. Then she took it upon herself to convince the others in her family to let her learn to read. Eventually, she became a scholar not only in Telugu but also in Sanskrit and English, and authored a valuable historical work, Abala Saccharitra Ratnamala. Tharu and Lalitha stated that Acchamamba intended to write three volumes [Biographies of women in classics, Women in History, and Biographies of foreign women] but completed only the first volume, and met with a premature death at the age of 30. She was also the first Telugu woman to start an organization for women in 1902.

Lakshmikantamma cited several instances in Andhra kavayitrulu Telugu Poetesses) where the family members had actively supported women’s education and encouraged creative writing. It would also appear that, by this time, the female scholarship extended, beyond Brahmin and Kshatriya castes, to other economically advantaged classes.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Kandukuri Veeresalingam (1848-1919) initiated the women’s education movement in Andhra Pradesh. His call for social reform included women’s education, widow remarriage, and eradication of prostitution. He advocated that, “the country cannot prosper unless women are educated.” His

In his autobiography, Veeresalingam paid tribute to his wife, Rajyalakshmamma. He stated that she was actively involved in his activities and supported his reform movements.

Veeresalingam’s proposition however was not accepted by all the elitists of his times. Kokkonda Venkatratnam Pantulu (1842-1915) was one of his staunch opponents in regard to education for women. In his magazine, Andhra Bhasha Sanjivani, Venkatratnam Pantulu published articles on the negative effects of women’s education at the same time while Veeresalingam striven to promote the positive side of it. That appeared to be only lip-service, according to V.R. Narla and Kanuparti Varalakshmamma.

Narla Venkateswara Rao, better known as V. R. Narla (1908-1985), an eminent journalist and Western-educated scholar, reported the debate between Veeresalingam and Venkatratnam Pantulu as follows [original text in English]:

The biggest and the most long-drawn-out of his battles were for the right of a woman to education and of a widow to remarriage… The degradation of India, he affirmed, had started from the day woman was reduced to an inferior status. … A controversy was then raging in two journals, Andhra Bhasha Sanjivani and Purushartha Pradayini, on the desirability or otherwise of giving education to women. Veeresalingam jumped into the fray with his wonted zeal.

About this time he launched his Sati Hitabodhini, a monthly journal exclusively devoted to the service of women. … In its columns, he serialized his stories of Satyavati and Chandramati, his biographical sketches of famous women, Indian and foreign, his popular guide to health, his moral maxims in verse, and his many other writings meant exclusively for women.

Notably, Veeresalingam’s course content of the education for women was not as progressive as his views on the need for women’s education. In his magazine for women, Sati Hitabodhini, started in 1883, he made his views clear in his article entitled “Uneducated women are their children’s enemies”. Veeresalingam stated, “If women are educated, they will refrain from using foul language and getting into brawls; and they will behave prudently and calmly. We have a proverb, ‘children take after their mothers.’ If women behave well, their children also will adapt to good behavior. … If mothers are stupid and petulant, their children fail in school, act cantankerously, take to evil ways, hurt others, and hurt themselves.” Veeresalingam’s views on female virtue raised some controversy in his later years.

Women started writing and publishing during Veeresalingam period. This could be construed as the first departure from tradition in the history of women’s writing. Lakshmikantamma mentioned that she owed her interest in the female writers of the past and that she owed it to Veeresalingam’s writings. In her article, Naati Vidushimanulu [Female Scholars of His Period], she wrote about several women writers and their works, including the writings of Rajyalakshmamma, Veeresalingam’s wife.

Initially women were writing on the same topics and expressing the same views as Veeresalingam. For example, some of the articles written by women during this period, “Ahalyabai” [story of Ahalya, a chaste woman in Hindu mythology], “Bhaktimargamu” [tenets of devotion], and “Satidharmamulu” [duties of wife], reaffirm his views on woman’s duty to her husband and family.

*****

(Contd..)

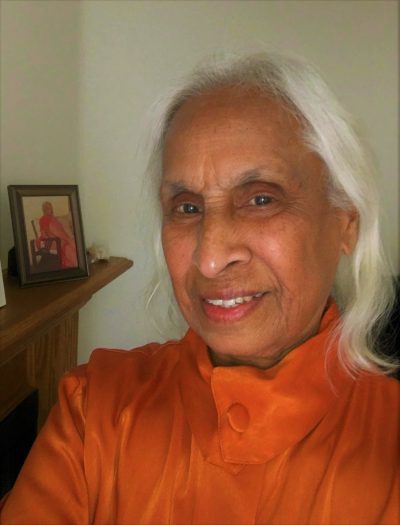

Nidadavolu Malathi born in 1937 to progressive parents, Nidadavolu Jagannatha Rao garu and Seshamma garu. She has Masters’ degrees in English Language and Literature, and in Library and Information Sciences. She has been writing fiction in Telugu since early 1950’s.

She moved to America in 1973. In 2001, she created a website, www.thulika.net, with a goal to introduce Telugu culture and customs through translations of stories and original essays on various topics. She has translated over 100 stories and wrote several critical essays. The website has been a good source for researchers in several universities abroad. In 2009, she started her blog, Telugu Thulika (www.tethulika.wordpress.com) where she has been publishing her Telugu stories, essays and poetry.

Her translations have been published in 2 anthogies, From my Front Porch (Sahitya Academy), and Penscape (Lekhini, Hyderabad). Her short stories in Telugu are published in 2 anthologies, Nijaanikee Feminijaanikee Madhya (BSR Publications) and Kathala Attayya garu (Visalandhra). She also has published eBooks: Eminent Telugu Scholars and other Essays (Non-fiction), All I Want Was to Read, My Litttle Friend (Short Stories.)