Telugu Women writers-14

-Nidadvolu Malathi

Use of Pseudonyms

Use of pseudonyms in the latter half of the twentieth century requires special mention. Unlike in the United States and Great Britain, Telugu women writers did not use male pseudonyms. Those who used pseudonyms picked only female names. For example, Aravinda (A.S. Mani), Syamala Rani (Akella Kamala Vijayalakshmi), Sarvani (Nilarambham Saradamma) and Bomma Hemadevi (Bomma Rukmini) are some of the pseudonyms used by female writers. Hemadevi mentioned that Hema was her daughter-in-law’s name! There is however no clear explanation why they chose to use pseudonyms. There was no indication it was due to fear of ridicule. From my interviews, it was obvious they did not hide their writing activities.

There is one writer, M. Padmavati, who has been writing under the pseudonym Vachaspati, which stands for Brahma, husband of Saraswati, Goddess of learning. Since the two names, Vacaspati and Saraswati are onomatopoeic, I wonder if it was intentional.

Malayavasini said that male writers using female pseudonyms started in the forties when women’s magazines proliferated, and the editors could not find enough women contributors to fill the pages. Setti Lakshminarasimham translated the novel, Hounds of Baskerville, under the title, Jaagilamu, and published it in his sister’s name, Seeram Subhadramba.

A unique phenomenon of this period is the use of female pseudonyms by male writers. In the fifties and sixties, some of the famous male writers like Rachakonda Viswanatha Sastry (Kantaakanta, Jasmine), Puranam Subrahmanya Sarma (Puranam Sita, his wife’s name, Sita Mahalakshmi), Akkiraju Ramapati Rao (Manjusri), and Natarajan (Sarada) used female pseudonyms. Viswanatha Sastry mentioned in a conversation with me that he had started writing under the pseudonym in order to get the magazine editors’ attention.

Discussion on pseudonyms is not complete without reference to Binadevi, a name that is still under fire. Binadevi has been writing since mid-sixties. In the past, it was believed that the actual writer was her husband, late B. Narsinga Rao, a judge by profession, and that he made up the pseudonym in order to circumvent the administrative issues. Secondly, to pass his wife, Balatripura Sundaramma as the original author because of the popularity of women writers. His wife, Balatripura Sundaramma is writing under the same pseudonym after her husband’s death. In 1999, she has received the Rachakonda Viswanatha Sastry award.

In Andhra Pradesh, we have several couples who are also writers. In some cases, they both were writing before they were married. Rumors of husbands writing under the names of wives have been prevalent in cases where both husbands and wives were writers but hard to substantiate. We also have couples, who write under their own names. Some of the notable couples are Polapragada Satyanarayana Murthy and Rajyalakshmi, K. Ramalakshmi and Arudra, R. Vasundhara Devi and R. S. Sudarsanam. Strangely, no controversy flared up in the case of these couples as in the case of Binadevi.

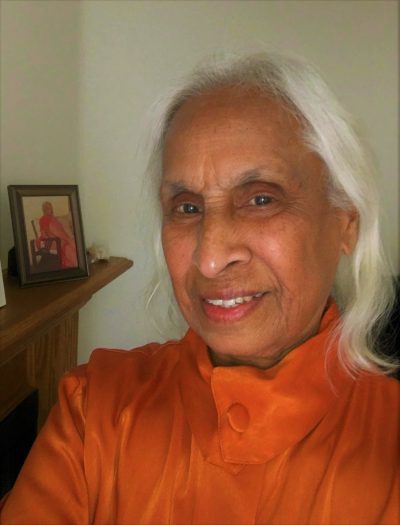

One of the peculiarities of Telugu women writers, starting in the nineteen fifties, was to redefine the family values while expressing their non-traditional and even controversial views. Most of the writers maintained traditional values for all appearances. They stayed home, cooked meals, took care of children, and would not leave home without their husbands by their side. Only few were willing to participate in public meetings (Nayani Krishnakumari, Utukuri Lakshmikantamma, K. Ramalakshmi, C. Anandaramam, and D. Kameswari, for instance). Some of them would not publish their photos in newspapers and magazines (Malati Chendur, Ranganayakamma, and Sulochana Rani, for example), although they enjoyed enormous recognition early in life as writers.

So far, I have presented several perspectives, conflicting at times, rather intentionally. My purpose is to illustrate the multifarious perceptions and attitudes prevalent in our culture. In the medieval period, women created their own world when they stayed home and limited their poetry to themselves; it was a personal journey. In the early fifties, the women writers kept part of these values from the preceding centuries while modifying a few to meet their new perceptions of the world around them.

Publishing their stories was a major breakthrough for women writers in the fifties. The second striking difference from the writers of the past was their awareness of identity, which surfaced during the freedom movement. After the British left and the democratic principles were put in place, the individual became the nucleus. Since both men and women participated in the freedom struggle, and men encouraged women, self-awareness became a natural outcome in both the cases. Women started perceiving themselves as individuals. That was evident in the writings of women writers of the nineteen fifties in their choice of themes and their diction.

*****

(Contd..)